Room rearrangement and indoor environment exploration

We investigate the problem of room rearrangement, where an agent explores a room, then attempts to restore the objects in a room to their original state.

Introduction

In this project, we investigate the problem of room rearrangement. In this task, an agent first explores a room and records the configurations of objects, using visual information available to it including RGB images and depth maps. After changing the poses/states of some objects in the room without the agent present, the agent must then restore the room to its original state.

In particular, we will study the improvement that applying various techniques brings, including discussing the incredible performance improvements that utilizing contrastive language image pretraining (CLIP) embeddings bring. This fundamentally simple, yet extremely effective technique has found to be effective in varied applications, from the image recognition tasks where it outperforms supervised models, to other natural language tasks like visual question answering. It has even been applied in image generation tasks, including StyleGAN image manipulation and prominently, the recent explosion in image generation models like DALLE-2 and Stable Diffusion [Khandewal].

We will also study the design of successful agents. With as complex of a task as room rearrangement, succesful agents may combine several reinforcement learning techniques to build submodules to solve subtasks that ultimately build to accomplish the full task.

Environment

Our explorations will be based on the AI2-THOR open source interactive environment, which allows for AI agents to interact with a realistic 3D environment, with many built in tools for checkpointing and validation. Agents have 82 actions available to them, including moving, rotating, and/or looking in any direction, and manipulating objects in the environment. We will use the RoomR dataset compiled by [Weihs et al., 2021].

Task

Given some environment consisting of a room and some number of objects, the agent has to complete two phases. The first phase is the “walkthrough” phase, where our agent explores the room, and observes the objects in their intended goal state. The second phase is the “unshuffling” or restoration phase, where a random number of objects in the room are changed, between one and five objects. The goal is to not only identify which objects have changed, but to manipulate the objects to restore them to their initial state in the walkthrough phase. Objects may be changed by moving its position, rotating or otherwise changing its orientation, or modifying some aspect of the object, including opening/closing the object.

After some initial exploration, we decided to evaluate the simpler variation of the problem. Instead of performing two separate, distinct stages, one walkthrough and one restoration, the “1-phase” challenge merges both phases into one. In this simplification, the agent has access to one RGB image from the goal state as well as one image from the shuffle state simultaneously, and need not make two trips throughout the environment to first gather data, and then perform the manipulations. We decided to make this simplification to lower model complexity.

Agents receieve three types of input from the environment: 224×224×3 RGB image, 224x224 depth maps, and a 1x6 AgentPose state vector that details the exact location and rotation of the agent.

Example RGB sensor input:

Example depth map sensor input:

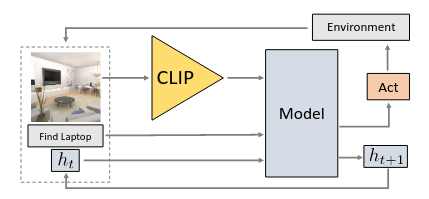

Model Overview

The various agents tasked with solving this problem have a similar fundamental structure. Essentially, the agent must know how to encode the 224x224x3 RGB images into a “perception” unit, and reason over time with a “planning” unit. For the 1-phase variation of this task, since images are simultaneously available from the goal state and the current state, there is no need to record information about the goal state. However, for the 2-phase task, the agent design must be modified to also record some semantic understanding of the goal state, or the saved goal state images from the walkthrough phase, which adds additional complexity not mentioned here.

Perception

The perception component of the agent must take in the 224x224x3 RGB image and discern important information like the objects in the current view, as well as depth and positional information. The agents we are studying have two primary techniques for achieving this encoding - a pretrained ResNet50 model, trained using traditional supervised learning, as well as utilizing a CLIP visual encoder. In the general model shown above, the CLIP visual encoder can be substituted for another visual encoder such as ResNet18 or ResNet50. Adjacent to the perception unit is an attention mechanism for image comparison.

ResNet

One of the leading CNN backbones, ResNet has proven to be adept at encoding visual information. In our baseline models, we evaluate agents that utilize ResNet as a visual encoder.

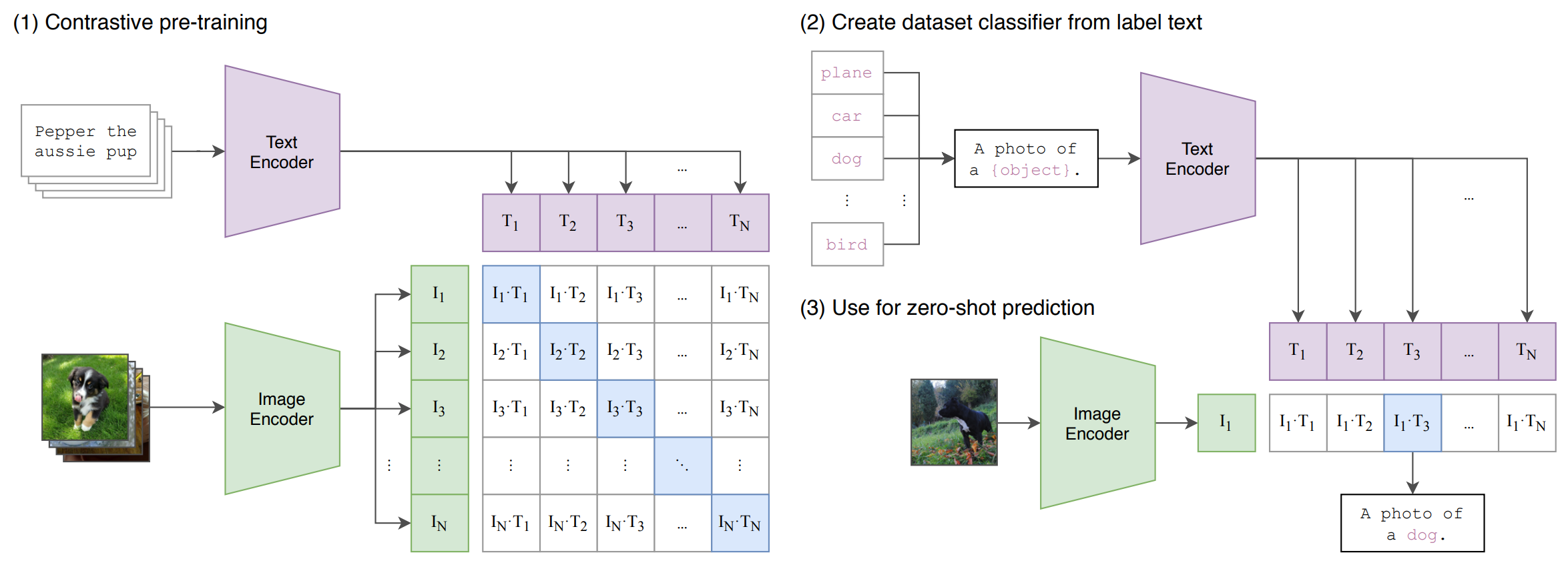

CLIP

At its heart, the ideas behind contrastive language image pretraining are fairly simple. CLIP encoders are trained on image-caption pairs, and learns to distinguish between image-caption pairs that correlate and image-caption pairs that contrast. Scaled up to a training dataset of 400M image-caption pairs, the result is a visual encoder that is incredibly adept. For example, when evaluated on the ImageNet benchmark, in zero-shot setting (no additional training), a CLIP visual encoder outperformed a fully supervised ResNet50 model.

CLIP architecture:

In this application, CLIP is similarly pitted against ResNet50 above as a visual encoder. It is hypothesized that CLIP’s superior semantic understandings will give it an edge over ResNet50 based agents.

Planning

With both agent position information and encoded visual information, the agent must be able to reason over time. However, since the problem cannot be described by a Markov decision process, we must also utilize a Long Short-Term Memory.

| The agents under comparison are all actor-critic agents. Given observations $\omega_t$, a history $h_{t-1}$, our actor-critic agent produces a policy $\pi_{\theta}(\omega_t | h_{t-1})$ and a value $v_{\theta}(\omega_t | h_{t-1})$, where $\theta$ is a generalized set of parameters. |

While agents can use some combination of techniques like PPO, Imitation Learning, and DAgger, among others, the primary agents we study use imitation learning, with expert actions provided by another reinforcement learning agent that acts with perfect information of the objects in the scene. This agent simply picks the closest, incorrectly placed object, navigates to it, and corrects its location.

Evaluation

We will score our different models on a few key factors. One ambitious overall metric is known as Success, or simply whether or not all objects are in their goal states at the end of the agent’s actions. However, this metric is quite unforgiving. If objects are in the correct position, but not in the correct orientation, that object is still counted as incorrect. A more nuanced metric is % fixed, which records the proportion of objects that had their pose fixed. Another metric is known as Misplaced. This metric counts the percentage of objects that are simply misplaced, giving us more information about how the model performs. Finally, a metric called energy places a limit on the amount of actions that can be performed.

Experiments

We will compare agents utilizing CLIP as a perception backbone versus agents utilizing ResNet50, which were previously shown to be the best performing.

Training

We train all agents on an AWS EC2 instance. We use the AllenAct framework to create our agents—this framework provides on-policy and off-policy algorithms as well as convenient plugins for Unity visualization. To view agent behavior, we X-forward this Unity-based visual output to a local machine.

Visual output while computing inference for agent with 8 parallel processes:

Dataset

The RoomR dataset contains pre-split data with train, test, and val splits. Each dataset split uses different floor plans. There are 4000 episodes in the train split and 1000 episodes in each of the test and val splits.

Running on AWS

To run experiments on AWS, we created an EC2 instance with the following AMI and instance type. Any G4 instance type (with NVIDIA GPU) will suffice.

# Deep Learning AMI GPU TensorFlow 2.10.0 (Ubuntu 20.04) 20221104

# g4dn.xlarge

Since we are running headless, we install X-server tools:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install xorg

Then, we clone the environments and install the dependencies:

git clone https://github.com/allenai/ai2thor-rearrangement && git clone https://github.com/allenai/allenact

cd ai2thor-rearrangement

pip install -r requirements.txt

However, because the latest version of torch (1.13.0) is compiled against a newer version of cudnn, we override the torch installation:

pip install torch==1.12.0

Finally, we include the ai2thor-rearrangement directory in the Python path:

export PYTHONPATH=$PYTHONPATH:$PWD

After completing these steps, we use the allenact framework to train our agents.

Results

| Perception Backbone | Proportion Fixed | Success Rate | % Misplaced | Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imitation Learning + CLIP | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| Imitation Learning + ResNet50 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 1.05 | 1.06 |

| Imitation Learning + ResNet18 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 1.09 |

Comparing different perception backbones, we can clearly see that CLIP provides a massive improvement, with almost 2x improvement over ResNet-based methods, all else being equal. Not only is the overall success rate higher, but other metrics like energy and % misplaced are lower. This is likely due to the additional semantic information that CLIP is able to encode, which ResNet is not capable of. Even making ResNet deeper, by using ResNet50 over ResNet18, does not produce nearly the same magnitude of result.

After analyzing the final states of objects within the environment, we also observed the majority of fixed objects were objects which change state but do not change location. In other words, the 62 pickupable objects had worse success rate than the 10 opennable objects. Intuitively, this makes sense since it should be easier to learn a binary difference at a fixed location.

Conclusion

Overall, we demonstrated CLIP provides an advantage over two forms of ResNet visual encoders. However, objectively, neither method is successful enough to apply practically. Moreover, we only experimented with the 1-phase version of the challenge. In theory, the 2-phase version should be more realistic and generalizable; however, we would expect even worse results using similar agents on this version of the challenge.

Additionally, one of the biggest challenges we faced working on this project was setting up the environment to train agents. The environment, framework, and many of their dependencies are all created by Allen AI. Despite this uniformity, we spent considerable time debugging dependency and setup issues before we were able to train our agents. We initially tried to run the environment locally, on Colab, and on GCP before finding the best performance on AWS. Moreover, we tried to run both the 2021 and 2022 versions of the challenge but were plagued with dependency issues on most platforms.

We also spent a lot of time training our agents. Because of computational/financial limitations, we were unable to perform more experiments with more agents. In future extensions of this project, we could try different pretrained CNN backbones in addition to other RL algorithms.

References

[1] Weihs, L., Deitke, M., Kembhavi, A., & Mottaghi, R. (2021). Visual Room Rearrangement (Version 1). arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2103.16544

[2] Dhruv Batra, Angel Xuan Chang, S. Chernova, Andrew J. Davison, Jun Deng, Vladlen Koltun, Sergey Levine, Jitendra Malik, Igor Mordatch, Roozbeh Mottaghi, Manolis Savva, and Hao Su. Rearrangement: A challenge for embodied ai. arXiv, 2020.

[3] Apoorv Khandelwal, Luca Weihs, Roozbeh Mottaghi, Aniruddha Kembhavi. Simple but Effective: CLIP Embeddings for Embodied AI. arXiv, 2022.