Explore Human-agent Interactions in Real-life Traffic

In this project, we study the effects of cooperation between multi-agent in avoiding real-world traffic collisions. We consider the following two questions: (1) Is cooperation among agents helpful in terms of reducing the collision rate? (2) Is it safe to keep human drivers involved in a multi-agent system?

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Related Works

- 3 Methodologies

- 4 Reinforcement Learning Models

- 5 Nocturne Environment

- 6 Experiments

- 7 Conclusion & Future Works

- Video Presentation

- Reference

1 Introduction

We study the interactions between humans and AI agents in real-life traffic, which is considered to be extremely dynamic and intractable in general. While autonomous driving has become increasingly popular in the past decade, it also raised safety concerns such as whether human and AI-driven cars can safely share the road. Our project concerns two questions: (1) Is it safe to keep human drivers involved in a multi-agent system? (2) Is cooperation among agents helpful in terms of keeping the road safe? Both questions can be answered through comparative studies. For the first question, we vary the ratio of human vs. agent drivers and see if it affects the collision rate. For the second question, we may as well check the change in the collision rate when cooperation is allowed. Conceptually, the agents may benefit from human behaviors through imitations, and information sharing allows them to further decrease the risk of accidents by planning routes early. On the other hand, human behaviors can sometimes be unpredictable, which prohibits agents from exploring more efficient driving strategies. Our work is important for several reasons. First, it offers a prediction of traffic safety when the number of self-driving cars increases, which is very likely to happen in the near future. Second, our results on the cooperation may provide insights for autonomous vehicle companies on whether or not to incorporate cooperation into self-driving cars, given that the implementation of real-time communication can be expensive in reality.

We will first review some related works on multi-agent cooperations and imitation learning and then introduce the methodologies that allow us to vary the ratio of human vs. agent drivers and share information among agents. We also review the Deep-Q learning model and propose a method to reduce the dimension of action space by decoupling independent actions. We finally present some experimental results based on the Nocturne environment, which provides further insights into human-agent interactions.

2 Related Works

We first review previous works related to multi-agent cooperation and imitation learning that are relevant to human-agent interactions. A recent work [5] adapts the policy gradient approach and uses a centralized action-value function to aggregate the states and actions from other agents. An algorithm called the multi-agent deep deterministic policy gradient was developed and was shown to attain significantly better performance than previous decentralized RL methods. [11] further scales up to RL with a larger number of agents by employing the idea of attention mechanisms.

An early method combines human knowledge into RL by designing reinforcement functions [8], but it involves the encoding of domain knowledge. More recent approaches include the use of GAIL and Human-in-the-loop learning that embody the expert data and decisions into the RL process; see [12, 7] for details. Other related works include [4, 9].

3 Methodologies

In this project, we will consider a more fundamental framework called the Deep-Q Learning, which is a value-based approach that uses neural networks to represent the policies in Q-learning. We next introduce methods to empirically study the aforementioned two questions.

One essential question is whether an agent drives more safely when it is surrounded by human drivers. If so, how will the number of human drivers affect the performance of the agents? This requires us to conduct comparative studies on the varying ratio of humans and agents in a driving scenario. More specifically, we compare the following safety metrics that measure how safely the agents drive: episode rewards that records the average reward at each step in an episode, collision rate that reflects how likely a collision – either between an agent and a curb or between two agents – will happen, and goal rate that reflects how many agents can reach the desired location in a limited period of time. Depending on the number of agents in a scenario, we consider the following three categories of models assuming a total of \(N\) vehicles in a scenario:

- Single-agent Model (Baseline): we randomly pick one vehicle and make it a controllable agent. The agent needs to learn an optimal policy such that it tries to reach the goal without colliding with other human drivers. All other unpicked vehicles will follow expert actions.

- Hybrid Model: we randomly pick \(M\) (\(1<M<N\)) vehicles to be controllable agents. For each agent, we need to find an optimal policy that maximizes the possibility of reaching the goal without collisions. All other unpicked vehicles will follow expert actions.

- All-agent Model: all \(N\) vehicles will be controllable agents. Similar to the Hybrid Model, the agents should develop policy to reach their goals without collisions.

Note that the Single-agent model and the All-agent model can be viewed as the Hybrid model with \(M=1\) and \(M=N\). We are particularly interested in the correlation between the safety metrics and the number of agents (\(M\)).

Cooperation is feaisble when multiple agents are present in a scenario. To see the effectiveness of cooperation, we can compare the safety metrics between a model without cooperation and a model with cooperation.

4 Reinforcement Learning Models

4.1 Deep-Q Learning

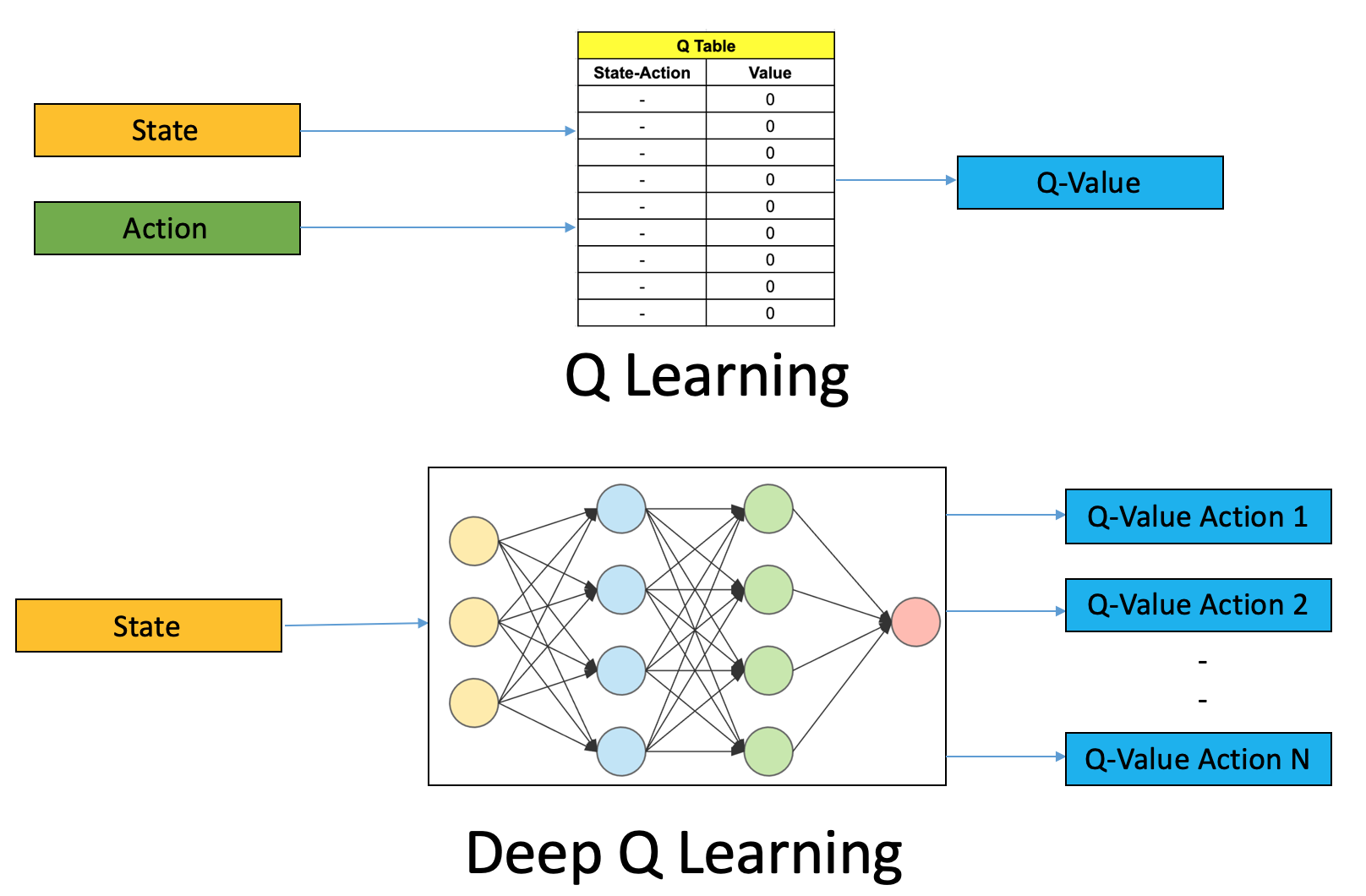

Q-learning is a commonly used model-free Reinforcement Learning algorithm. The Q-learning method is able to learn values for actions in given states through a Q-table. However, when the number of actions and number of states is large, Q-learning starts to show its restriction, as millions of cells in the table will be created, and the computational cost is going to be uncontrollable. The Deep Q-learning model provides treatment by approximating Q-values with neural networks, which are also called Deep-Q networks (DQNs).

Figure: Q-Learning vs Deep Q-Learning from [15].

According to the figure, the Deep Q-Learning approximates Q-values for each action based on the input state, which is in contrast to the vanilla version of Q-learning that predicts the Q-value by looking up a Q-table. Moreover, we use a replay buffer, an array-like data structure, to store the state-action pairs from past experience. This is only necessary since Deep-Q learning is an off-policy RL method: \(\epsilon\)-greedy is used for the behavior policy and the action with maximal Q-value is always chosen for the target policy. The Bellman equation for each update is expressed as follows

\[Q(S_t,A_t) \leftarrow Q(S_t, A_t) + \alpha[R_{t+1} + \gamma \max_a Q(S_{t+1}, a) - Q(S_t, A_t)]\]4.2 Decoupled Action Space

The prediction of Q-values using DQNs can be considered a regression problem (with continuous outputs), which is often considered hard to solve especially when the output space is large. In this case, the output dimension of the DQN is exactly the dimension of the action space. Therefore, the difficulty of optimizing the DQN increases when the number of actions is huge. We propose a simple way to decouple the action space by imposing certain independence assumptions upon the action space.

Suppose there are \(t\) classes of actions denoted as \(\mathcal{A}_1,\dots, \mathcal{A}_t\), then the original action space is defined as the cartesian product of these actions, i.e. \(\mathcal{A} = \mathcal{A}_1 \times \cdots \times \mathcal{A}_t\). For instance, if a vehicle has 10 different acceleration actions and 20 different steering actions, there will be a total of 200 different actions. It is evident that the dimension of the action space grows exponentially in the number of action classes (\(t\)). Fortunately, the exponential-sized action space can be avoided if we assume that the action classes are independent of each other. That is, conditioning on the input state, the action chosen in one class would not affect the actions chosen in other classes. For instance, given the current state of the vehicle, the adjustment of acceleration will not affect the vehicle’s steering. Under the independence assumption, we can then decouple the action space into independent action classes. The action space can now be decomposed into \(\mathcal{A}_{ind} = \mathcal{A}_1 \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathcal{A}_t\). The dimension of the action space becomes linear in the number of action classes. For the same vehicle example, the size of the action space is reduced to 30.

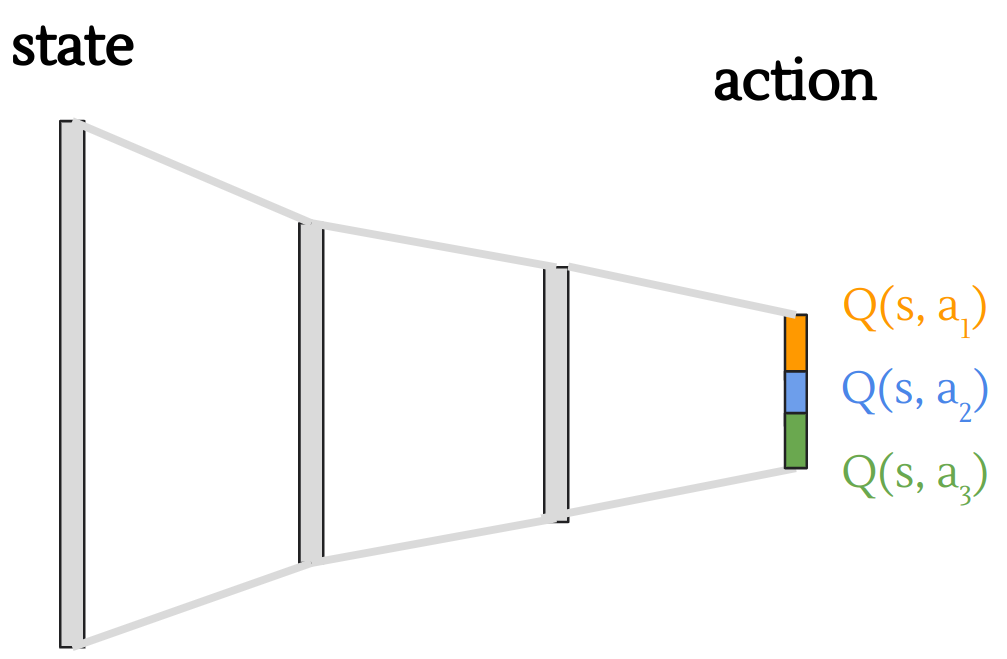

To compute the Q-value for a specific action \(a \in \mathcal{A}_{ind}\), we first decompose it into sub-actions \(a_1 \in \mathcal{A}_1, \dots, a_t \in \mathcal{A}_t\) and then compute the Q-value of each sub-action. This can be done very efficiently using a single DQN with segregated output; see the following figure for an illustration.

Figure: DQN for decoupled action space.

The final Q-value can be obtained by summing up the Q-value for each sub-action

\[Q(s,a) = Q(s,a_1) + \cdots + Q(s,a_t)\]Note that the maximization of the final Q-value can be easily done by summing up the maximal Q-value for each sub-actions

\[max_a Q(s,a) = max_{a_1} Q(s,a_1) + \cdots + max_{a_t} Q(s,a_t)\]For the behavior policy, we apply \(\epsilon\)-greedy to each sub-action.

4.3 Cooperation

If we allow the agents to communicate with each other, then each agent can obtain information that is not directly observable by itself. The agents may also develop a cooperative strategy that leads to better road safety. More advanced cooperative learning has been developed previously, but we only consider a naive observation-sharing paradigm in this work.

Specifically, the state for each agent consists of two parts: its own observation and shared information from other agents. The shared information may include any features beneficial to the agent’s policy-making. For instance, the sharing of speed and direction may help agents maintain minimum distances from each other. We aggregate the shared information from multiple agents by simply concatenating the shared vectors, albeit attention mechanisms may be considered here to obtain a more compact representation. We also exploit locality when cooperation can be isolated to a small cluster of agents. For example, in the self-driving scenario, the policy of an agent should mostly be affected by its closest neighbors. This reduces the amount of information being shared, which also improves communication efficiency.

5 Nocturne Environment

We will use the Nocturne environment which is a 2D driving simulator built from traffic scenarios in the Waymo Open Dataset [1]. We consider the environment for several reasons. First, it mimics real-life driving scenarios where each agent has a cone-shaped view as shown in Figure 1. More importantly, we are allowed to change the number of controllable agents in the scene, and expert actions are provided for each uncontrolled vehicle.

Figure 1: A visual showing the traffic for a specific scene on the road (Left). And the obstructed view of the single viewing blue agent (Right).

Figure 1: A visual showing the traffic for a specific scene on the road (Left). And the obstructed view of the single viewing blue agent (Right).

Nocturne generates environments based on a set of initial and final road object positions and (optionally) a set of trajectories for the road objects obtained from the Waymo Motion Dataset [14]. The generated scenarios contain vehicles, roads, and other objects such as stop signs. Currently, Nocturne does not support traffic lights, pedestrians, or cyclists within the environment due to constraints from the Waymo Motion Dataset.

For state representations, Nocturne provides two different ways: an image and a vectorized representation of the image. For ease of use, we will be mainly using vectorized representation for training. Based on the environment and states, we are able to obtain the following state features for each vehicle:

- The speed of the vehicle

- The distance and angle to the goal position

- The width and length of the vehicle

- The relative speed and heading compared to the expert driver (human data)

- The angle between the velocity vectors of a specific vehicle and all other vehicles in the environment

- The angle and distance of a specific vehicle from all other vehicles in the environment

- Other road objects’ heading relative to the specific vehicle

And each vehicle in the environment can take the following actions:

- Acceleration: 6 values in range

[-3,2] - Steering: 21 values in range

[-0.7, 0.7](maximum 40 degrees) - Head angles: 5 values in range

[-1.6, 1.6]

Partial observability is achieved by setting a 120-degree view cone for the training agent. Within the 120-degree view cone, all vehicles that intersect with a single ray in the cone and are not blocked by other vehicles closer to the training agent are considered visible. During training, agents will only be able to obtain information from observable vehicles and are able to use head tilt action to adjust the view cone to obtain more information.

In terms of implementation, the Nocturne environment reads the specifications from a config.yaml file that defines hyperparameters such as the maximum number of controllable agents (\(M\)), the elements in the reward function, the goal condition, etc.. Once the program loads a scenario from the data file, it first eliminates those vehicles that are impossible to reach the goal position and then randomly selects \(M\) vehicles to be controllable agents.

The usage of the Nocturne environment is similar to the gym library, for example:

obs, rew, done, info = env.step({

veh.id: Action(acceleration=2.0, steering=0.0, head_angle=0.5)

for veh in moving_vehs

})

where obs, rew, done, info stand for observation, reward, done, information, repsectivley. More details are specified as follows

- Observation: A vector of dimension

13470, representing the driver’s view - Reward: A single Float value representing the reward

- Done: A Boolean representing if the agent reaches an end state

-

Info: Contains other useful information:

goal_chieved: A Boolean representing whether or not the goal is achievedcollided: A Boolean representing if collision occursveh_veh_collision: A Boolean representing if an agent collides with another vehicleveh_edge_collision: A Boolean representing if the agent collides with road edge

6 Experiments

6.1 Setup

Due to limited computational resources, we conduct experiments on a single scenario that contains 30 vehicles. For the first human vs. agents experiment, we randomly select \(n\in\{1,10,15,20,30\}\) vehicles to be controllable agents. For the cooperation experiment, we fix all 30 vehicles to be controllable agents and adapt the model to incorporate cooperation. For all experiments, we record the average collision rate, goal rate, and episode rewards over 80 episodes. We implemented a replay buffer of size 10000. The first 40 episodes are used to fill up the replay buffer and no update on the policy network is performed.

For the behavior policy, we use the \(\epsilon\)-greedy algorithm where the \(\epsilon\) exponentially decays from 0.9 to 0.1 in 7000 steps. To update the target policy, we first randomly sample a 256 batch and optimize the network parameters using an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of \(10^{-4}\). The discount factor in the Bellman equation is set to 0.9 and the target network is updated every 500 steps (to stabilize the training).

All experiments are conducted on a CPU with 32GB RAM. We run the RL learning algorithm until it consumes all the available memory. We also generate a video of the trajectory every 20 episodes.

6.2 Observations & Rewards

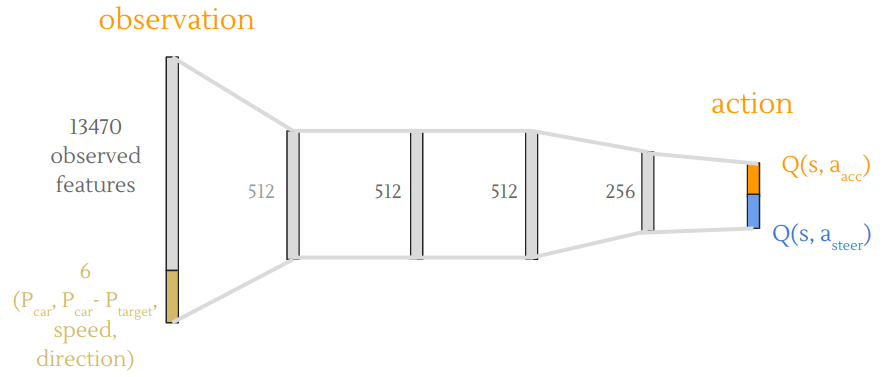

For the case without cooperation, the observation vector is defined as the initial 13,470 features from Nocturne concatenated with additional 6 features that describe the position of the vehicle, the position difference between the vehicle position and its goal position, the speed of the vehicle, and the direction of the vehicle. For the case with cooperation, we concatenate from the nearest 5 agents extra shared features including their position, speed, and direction, which produces an observation vector of dimension 13,496.

The design of the reward function is more subtle. We consider three components in the reward function: goal bonus if the vehicle reaches the goal, collision penalty if the vehicle collides with others, and distance reward when the vehicle moves towards the goal. The goal bonus and collision penalty are only activated when the corresponding events happen, while the distance reward is computed for each movement of the agent. We add a scaling factor of 10 to the distance reward. To illustrate, our reward function can be written as

\[R(s,a) = bonus_{goal}(s,a) - penalty_{collision}(s,a) - 10\Delta d(s,a)\]Specifically, the first two terms (bonus & penalty) are set to the maximum episode length (=80). The last term is computed as the change of the distance between the agent and goal, i.e. \(\Delta d = ||p_{target}-p(s')|| - ||p_{target}-p(s)||\), where \(p(s)\) and \(p(s')\) denote the position before applying the action and the position after applying the action. (credit: this formulation of distance reward was suggested by TA Zhenghao Peng, which turns out to be quite effective).

6.3 Model Specifications

Our DQN is a feed-forward neural network with 4 hidden layers with dimensions of 512, 512, 512, 256, respectively. The ReLU activation function is used for each hidden layer. We decided to fix the head angle to 0 so that the 120-degree cone is always directed towards the front of the vehicles. We also decouple the action space into separate sub-actions for acceleration and steering. See the figure below for the detailed design.

Figure: DQN architecture.

6.4 Results

We next present the results for the human vs. agents experiment and the cooperation experiment.

6.4.1 Human vs. Agents

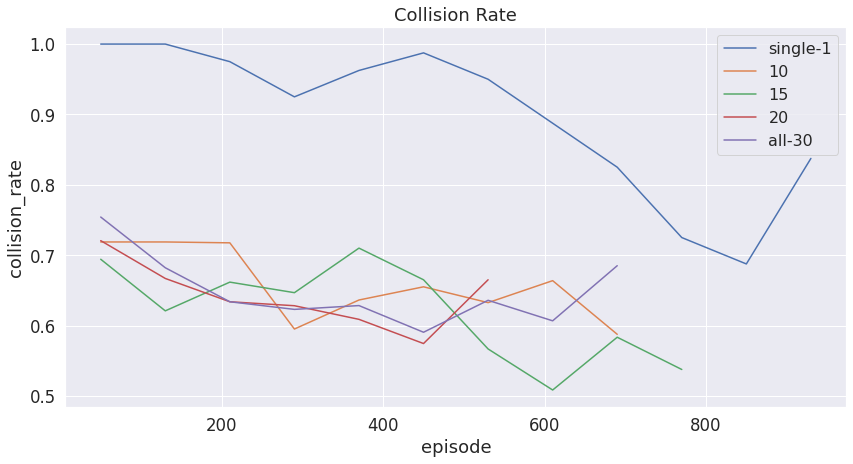

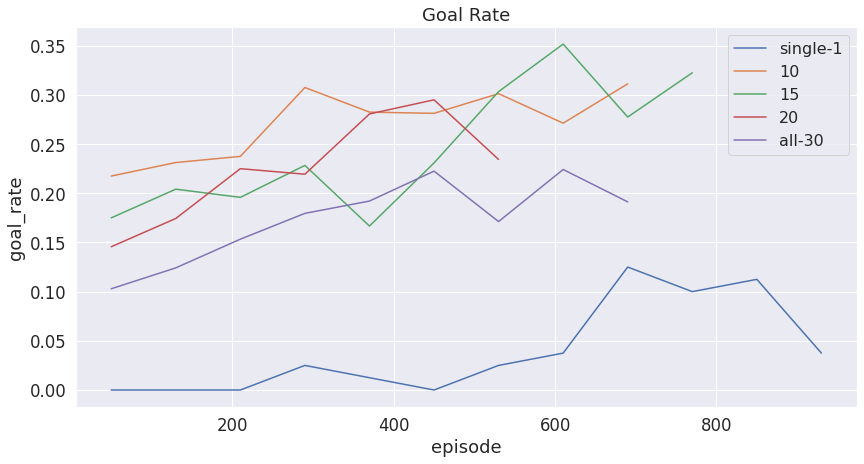

The following plots show the safety metrics (collision rate, goal rate, and episode rewards) under different numbers of agents in the total population.

Figure 6: Collision rate with more agents in the environment

Figure 7: Goal rate with more agents in the environment

Figure 8: Episode reward with more agents in the environment

As we can see, compared to only having one agent driven vehicle in the environment, multi-agent system have a lower collision rate and a higher goal rate. Among all the multi-agent systems, when half of the vehicles in the environment are driven by agents, we have the highest goal rate, lowest collision rate and higher episode reward. Compared to that, when all of the vehicles in the environment are agent driven, it does not perform as well as we expected, having lower reward, lower goal rate and higher collision rate compared to other multi-agent systems. This might be due to the limited size of the Neural Network we are using in the DQN and the limited computational resource we have to train for a long time.

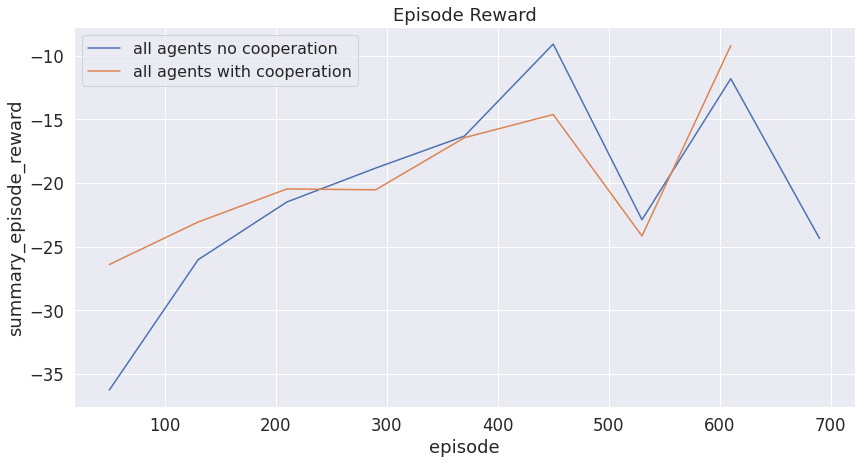

6.5.2 Cooperations

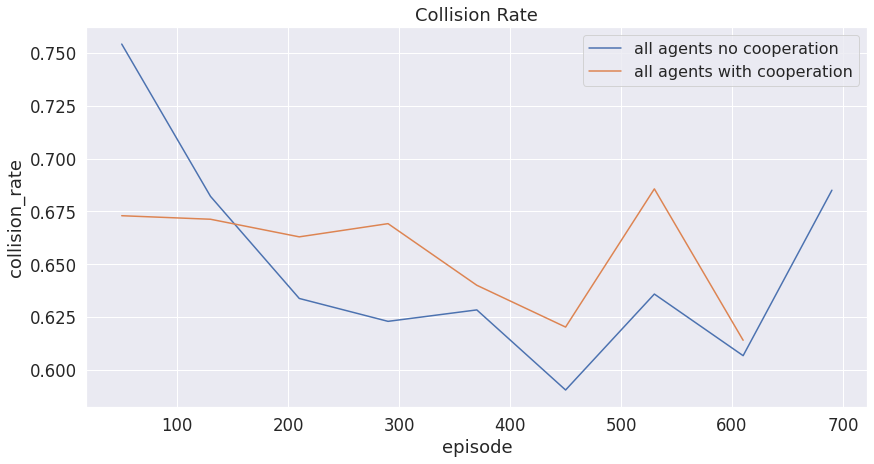

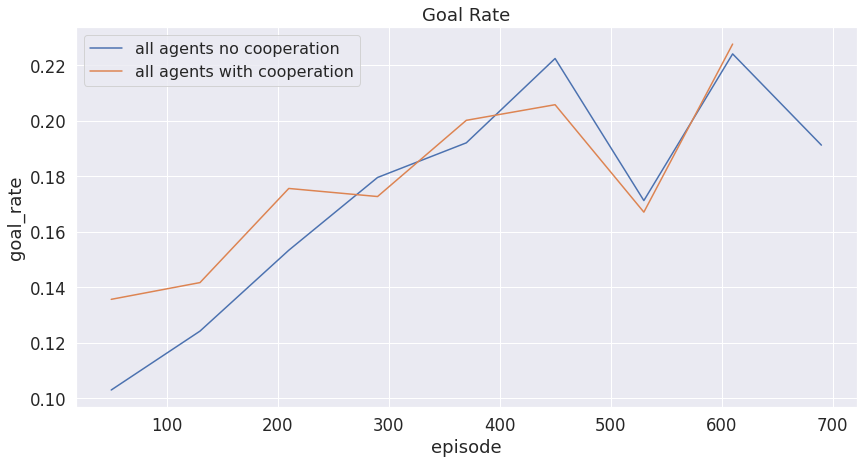

The following plots show the safety metrics when we incorporate cooperation. Note that we assume all the vehicles are controllable agents.

Figure 9: Collision rate of multi-agent system with cooperation vs without cooperation.

Figure 10: Goal rate of multi-agent system with cooperation vs without cooperation.

Figure 11: Episode reward of multi-agent system with cooperation vs without cooperation.

From all of the plots above, the current multiagent with a cooperation system failed to achieve better results compared to those without cooperation. This might come from three different reasons: 1) The information we share among vehicles is not sufficient enough for agents to learn from. 2) The Neural Network we have in DQN is not wide/deep enough to capture the added information. 3) Due to the limited computational resource we have, our implementation might be restricted to computing power, thus not being able to learn enough from the data.

7 Conclusion & Future Works

We explored the human-agent interactions from two angles, both of which provided insights into the road safety of self-driving cars. We first studied the effects of the human-agent ratio in an environment, and the experimental results showed that the best performance was reached when around half of the vehicles in the scenario were controllable agents. We also tried to integrate shared information into agents’ states, which, surprisingly, did not lead to any improvements. This can be due to the low expressivity of simple DQNs, the limited size of the replay buffer, or an insufficient number of epochs. Future works may include generalizing the models to more scenarios, utilizing more advanced RL models such as the centralized actor-critic algorithm, and training with larger replay buffers and more episodes if more computational resources are available.

Video Presentation

Reference

[1] Eugene Vinitsky, et al. Nocturne: a scalable driving benchmark for bringing multi-agent learning one step closer to the real world. 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.09889.

Github: https://github.com/facebookresearch/nocturne

[2] Waymo Open Dataset: https://github.com/waymo-research/waymo-open-dataset

[3] Christopher J. C. H. Watkins, Peter Dayan. Q-learning. Mach Learn 8, 279–292 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992698

[4] Volodymyr Mnih et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14236.

[5] Ryan Lowe et al. Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.02275.

[6] Alexey Dosovitskiy et al. CARLA: An Open Urban Driving Simulator. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2017. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v78/dosovitskiy17a/dosovitskiy17a.pdf.

[7] Quanyi Li and Zhenghao Peng and Bolei Zhou. Efficient Learning of Safe Driving Policy via Human-AI Copilot Optimization. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). 2022. https://openreview.net/forum?id=0cgU-BZp2ky

[8] Maja J. Mataric. Reward Functions for Accelerated Learning. ICML 1994. https://www.sci.brooklyn.cuny.edu/~sklar/teaching/boston-college/s01/mc375/ml94.pdf

[9] Ariel Rosenfeld and Matthew E. Taylor and Sarit Krau. Leveraging Human Knowledge in Tabular Reinforcement Learning: Study of Human Subjects. Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, {IJCAI} 2017, Melbourne, Australia. 2017. https://www.ijcai.org/proceedings/2017/534

[10] Ashish Vaswani et al. Attention is All you Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.03762.pdf

[11] Shariq Iqbal and Fei Sha. Actor-Attention-Critic for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2019. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/iqbal19a/iqbal19a.pdf

[12] J. Ho and S. Ermon, “Generative adversarial imitation learning,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 4565–4573, 2016.

[13] Stanford Course Project: https://web.stanford.edu/~blange/data/Data-Driven%20Multi-agent%20Human%20Driver%20Modeling.pdfw

[14] Ettinger, S., Cheng, S., Caine, B., Liu, C., Zhao, H., Pradhan, S., Chai, Y., Sapp, B., Qi, C. R., Zhou, Y., et al. Large scale interactive motion forecasting for autonomous driving: The waymo open motion dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (2021), pp. 9710–9719.

[15] Choudhary, A. A Hands-On Introduction to Deep Q-Learning using OpenAI Gym in Python. 2020. https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2019/04/introduction-deep-q-learning-python/