The Emergence of Roles in Multi-agent Traffic Learning

We are interested in applying role-based multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) to self-driven particle systems. Specifically, we are inspired by role-based hierarchical MARL frameworks (Wang et al., 2020a; Wang et al., 2020b), which explicitly models agents as having different roles, with each role having its own policy. In this way, the search space for the policy is greatly reduced as the joint action space for roles is much smaller than the joint action space for all agents. We hope to further explore this idea in the MetaDrive environment to study the emergence of roles in the traffic setting. In conclusion, our group hopes to apply various hierarchy-based MARL algorithms to autonomous driving scenarios, and compare our results with existing methods such as (Peng et al., 2021).

Motivation

MARL Background

Multi-agent collaboration scenarios are commonly observed in real-world applications, such as autonomous vehicle teams (Cao et al., 2012), intelligent warehouse systems (Nowe et al., 2012), and sensor networks (Zhang & Lesser, 2011). In recent years, multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), combined with deep-learning-based methods, has achieved prominent progress in simulating efficient collaborative behavior. However, one critical issue often encountered in multi-agent scenarios is called the curse of dimensionality — the observation space and action space increase exponentially with increased number of agents, putting great burden on the value and policy network training and thus negatively affect the efficiency. To deal with such issues, many recent methods apply a centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) framework. With CTDE, joint information regarding all agents is fed into the joint (centralized) evaluation network to ease training, while the evaluation is then decomposed into individual (decentralized) modes following which agents aim to improve their policies. The execution phase thus requires agents to act using only local information to satisfy the partial observability and communication constraints usually encountered in multi-agent situations.

Roles in cooperation

Cooperation is quintessential and commonly observed in human society. While facing complicated tasks, instead of planning actions from a holistic perspective, human teams usually form specific representation of subtasks. Individual teammates would then take on subtasks corresponding to the respective roles [8][9]. In this way, the joint task is indeed executed in a decenetralized fashion similar to the CTDE framework in MARL mentioned in the previous section. Such strategy of designing roles for partners further enables effective task allocation that enables certain agents to be specialized at certain tasks without distractions from other unrelated environmental information and thus further improve the team performance.

Combining roles with MARL

The idea of designing subtasks to handle multi-agent problems has been explored in MARL research. On the other hand, the majority of CTDE-based algorithms rely on deep neural networks to decompose the central evaluation with no specific guidance on how to decompose the team value meaningfully. The decomposition process remains a black box, which makes it hard to ensure these algorithms can achieve efficient cooperative behavior as humans do. With this mindset, our group explored a paper regarding role-based MARL: to learn roles for the task to guide agents’ behavior [5]. Under the framework of RODE, agents are explicitly modeled as having different roles, with each role corresponding to one specific policy. In this way, the search space for the policy is greatly reduced as the joint action space for roles is much smaller than the joint action space for all agents. At the same time, explicitly modeling roles can generate more interpretable policies, which resonates with real-life human cooperation. We then adapt and apply the framework to multi-agent autonomous driving scenarios, aiming to generate effective cooperation under various difficult traffic conditions. We further apply state-of-the-art MARL algorithms [4][7] as baselines to experiment on the effectiveness of role-based representations in traffic scenarios.

Related Work

Baseline: QMIX

Under the CTDE assumptions, the central evaluation structure incorporates concatenated information from all agents to estimate the team performance. The joint action-value function is then decomposed into subparts for each agent to execute in a decentralized fashion. Specifically, such decomposition-based methods rely on the assumption of Individual-Global-Max (IGM) [10], which enforces the consistency between joint and local greedy action selections in the joint action-value \(Q_{tot}(\tau, a)\) and individual action-value functions \([Q_i(\tau_i, a_i)]_{i = 1...n}.\) In this way, the assumption ensures that agents’ actions executed by the individual action-value functions are always positively contributing to the group performance as evaluated by the joint action-value function. The factorization process further contributes to the scalability of the model, allowing for easy adaptation to scenarios with a large joint action space, where individual agents may select actions locally in execution.

One classic framework using the IGM assumption is the value decomposition network (VDN), where the joint value function from the central critic is treated as a summation over all individual agents’ utilities [11]. Individual agents then take the argmax over their local action value functions to act in a decentralized way, without the need of information from other parts of the environment or other agents (Equation (1)). The algorithm QMIX extends the additive nature of individual value function composition in VDN to a monotonicity constraint, thus allowing for more flexibility in agents’ behavior [7]. Specifically, the value derivatives are fed through a ReLU network to ensure a monotonic mixing process, constraining individual agents’ utilities to be positively contributing to the joint utility (Equation (2)).

\[Q_{tot}^{\mathrm{VDN}}(\tau, a) =\sum_{i=1}^{n} Q_{i}(\tau_{i}, a_{i}) ( 1 )\] \[\frac{\partial Q_{tot}^{\mathrm{QMIX}}(\tau, a)}{\partial Q_{i}(\tau_{i}, a_{i})} \geq 0, \quad \forall i \in \{1...n\} ( 2 )\]To date, QMIX remains to be one of the most commonly used value-based MARL method that is effective under many multi-agent problems. In our project, we apply QMIX as one of the baselines to study the effect of roles in multi-particles driving scenarios.

Main Method: RODE

Role-based methods serve as a promising approach towards scalable MARL. In this project we explore one such method, RODE. In RODE, roles are defined based on actions-to-take. Specifically, the joint action space is decomposed into restricted role action spaces through clustering actions according to their effects.

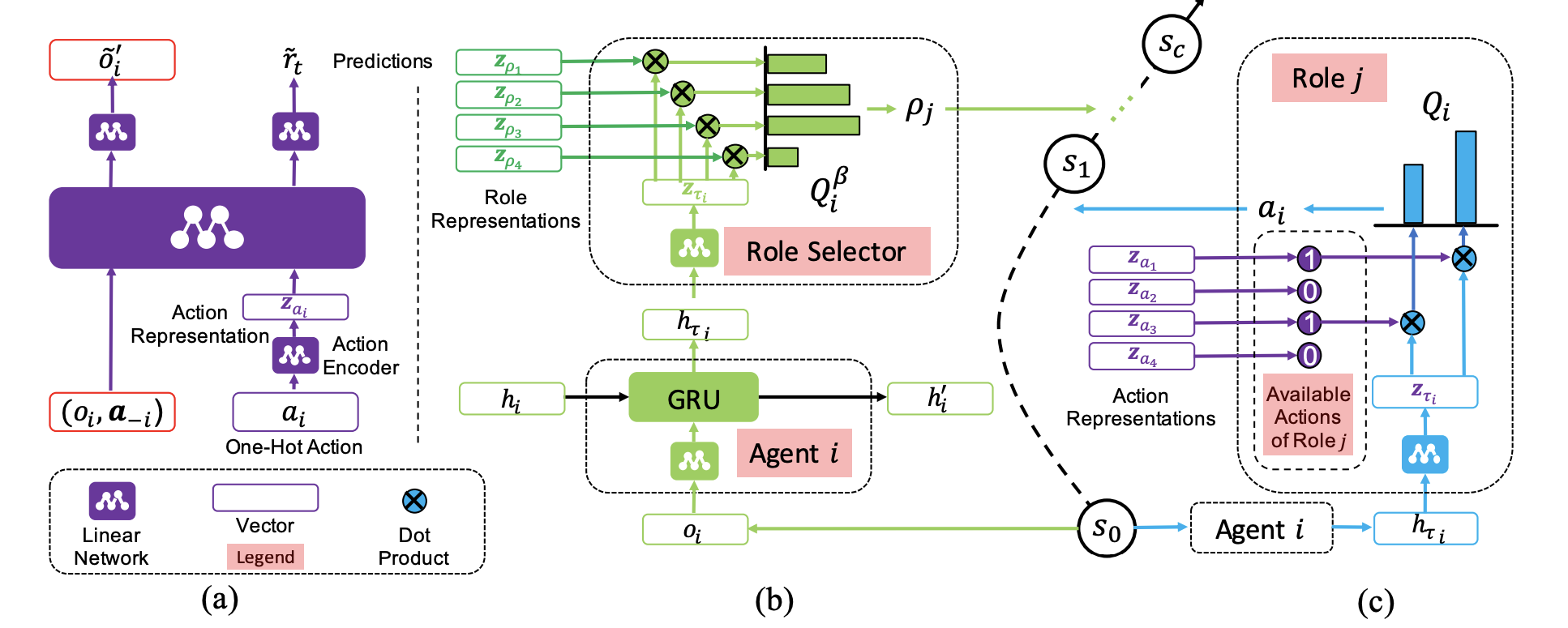

Fig 1. RODE framework. (a) The forward model for learning action representations. (b) Role selector architecture. (c) Role action spaces and role policy structure. [5].

Problem setup

Formally, RODE focuses on fully cooperative multiagent tasks that can be modelled as a Dec-POMDP [12] consisting of a tuple \(G=\langle I, S, A, P, R, \Omega, O, n, \gamma\rangle\), where \(I\) is the finite set of \(n\) agents, \(\gamma \in[0,1)\) is the discount factor, and \(s \in S\) is the true state of the environment. At each timestep, each agent \(i\) receives an observation \(o_i \in \Omega\) drawn according to the observation function \(O(s, i)\) and selects an action \(a_i \in A\), forming a joint action \(a \in A^n\), leading to a next state \(s^{\prime}\) according to the transition function \(P\left(s^{\prime} \mid s, a\right)\), and observing a reward \(r=R(s, a)\) shared by all agents. Each agent has local action-observation history \(\tau_i \in \mathrm{T} \equiv(\Omega \times A)^*\). Given a cooperative multi-agent task \(G\), let \(\Psi\) be a set of roles. A role \(\rho_j \in \Psi\) is a tuple \(\left\langle g_j, \pi_{\rho_j}\right\rangle\) where \(g_j=\left\langle I_j, S, A_j, P, R, \Omega_j, O, \gamma\right\rangle\) is a sub-task and \(I_j \subset I, \cup_j I_j=I\), and \(I_j \cap I_k=\varnothing, j \neq k\). \(A_j\) is the action space of role $j$, \(A_j \subset A, \cup_j A_j=A\). \(\pi_{\rho_j}: \mathrm{T} \times A_j \rightarrow[0,1]\) is a role policy for the sub-task \(g_j\) associated with the role. The goal is to learn a set of roles \(\Psi^*\) that maximizes the expected global return \(Q^{\Psi}\left(s_t, \boldsymbol{a}_t\right)=\mathbb{E}_{s_{t+1: \infty}, a_{t+1: \infty}}\left[\sum_{i=0}^{\infty} \gamma^i r_{t+i} \mid s_t, a_t, \Psi\right]\).

Learning action representations

Actions are first processed by an action encoder to generate latent representations, which are fed to a linear network. The encoder and the network are jointly trained by predicting the resulting environment observation and reward in the next step, to enforce the latent action representations to reflect the effects of actions on the environment and other agents. Specifically, defining roles can be considered as the process of factoring the action space according to actions’ properties, with roles focusing on actions with similar effects. In implementation, learning of action representations \(f_e\left(\cdot ; \theta_e\right)\) : \(\mathbb{R}^{|A|} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d\) can be achieved through a supervised fashion with a predictive model. The representation of an action \(a\) in this space is denoted by \(\boldsymbol{z}_a\), i.e., \(\boldsymbol{z}_a=f_e\left(a ; \theta_c\right)\), which is then used to predict the next observation \(o_i^{\prime}\) and the global reward \(r\), given the current observation \(o_i\) of an agent \(i\), and the one-hot actions of other agents, \(a_{-i}\). This model can be interpreted as a forward model, which is trained by minimizing the following loss function:

\[\mathcal{L}_e\left(\theta_e, \xi_e\right)=\mathbb{E}_{\left(o, a, r, \sigma^{\prime}\right) \sim \mathcal{D}}\left[\sum_i\left\|p_o\left(\boldsymbol{z}_{a_i}, o_i, \boldsymbol{a}_{-i}\right)-o_i^{\prime}\right\|_2^2+\lambda_e \sum_i\left(p_r\left(\boldsymbol{z}_{a_i}, o_i, \boldsymbol{a}_{-i}\right)-r\right)^2\right],\]where \(p_o\) and \(p_r\) are predictors for observations and rewards, respectively, and parameterized by \(\xi_e\). \(\lambda_e\) is a scaling factor, \(D\) is an replay buffer.

After the action encoder is trained, the encoded actions are grouped into K clusters using K-means clustering on the action latent representations.

Learning role policies

After clustering, a role’s representation is then defined as the average embedding of actions associated with the role, and the role representations are used to compute Q-values between each role-agent pair and assign roles to agents through the role-selector network.

Using action representations \(z_{a_k}\) and \(z_\tau\), the value of agent \(i\) choosing a primitive action \(a_k\) is defined as:

\[Q_i\left(\tau_i, a_k\right)=z_{\tau_i}^{\mathrm{T}} z_{a_k} .\]The local \(Q\)-values are then fed into a QMIX-style mixing network to estimate the global action-value, \(Q_{t o t}(s, a)\). The parameters of the mixing network are denoted by \(\xi_\rho\), which are trained to minimize the TD loss for learning role policies:

\[\mathcal{L}_\rho\left(\theta_{\tau_\rho}, \theta_\rho, \xi_\rho\right)=\mathbb{E}_{\mathcal{D}}\left[\left(r+\gamma \max _{\boldsymbol{a}^{\prime}} \bar{Q}_{\text {tot }}\left(s^{\prime}, \boldsymbol{a}^{\prime}\right)-Q_{t o t}(s, \boldsymbol{a})\right)^2\right] .\]Experiments

To study the emergence of roles in traffic learning settings, we apply the RODE framework to MetaDrive environments. Currently, we test our implementation on one existing MARL environment in MetaDrive, Bottleneck. We study the cooperative setting via summing individual agent rewards as the global environment reward and set the environment termination status once a single vehicle terminates. Since RODE assumes discrete agent action spaces, we discretize agents’ action spaces and set both steering and throttle dimensions to 5, which lead to a similar number of actions for each agent to RODE’s testing environment. During training, we set the maximum length of each episode to 200, and the training duration of the action encoder to 50000 environment steps.

Action Clustering

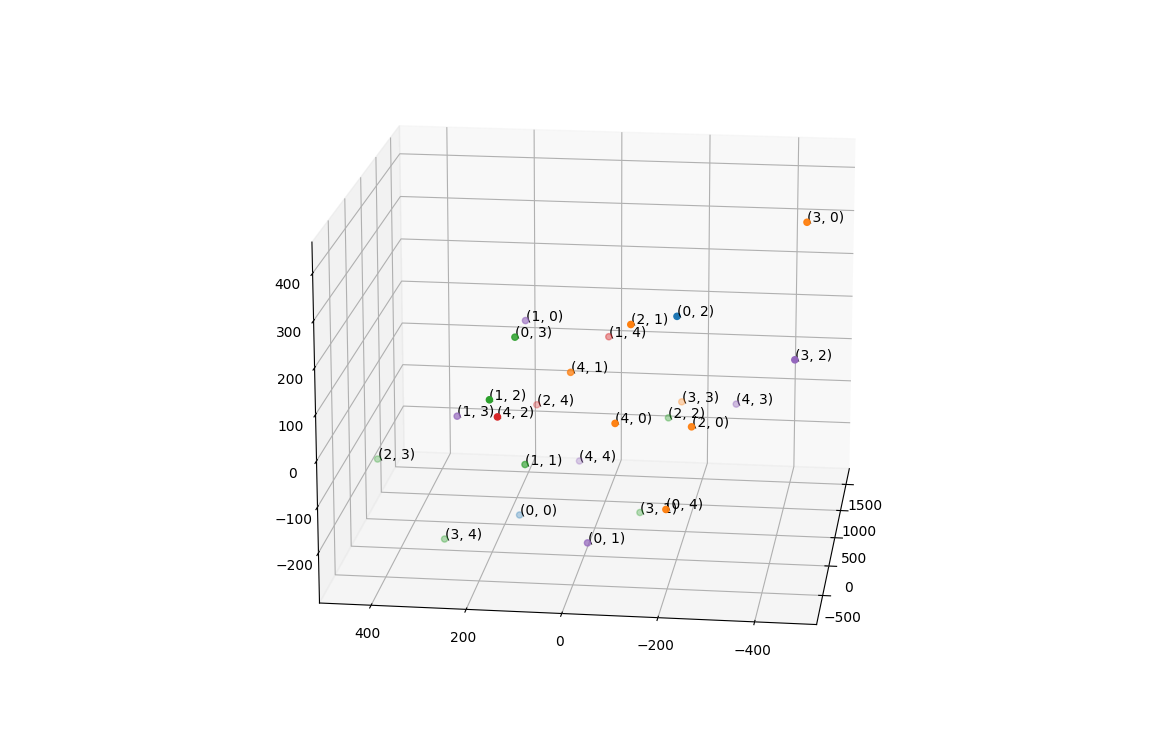

To study the semantics learned by the action encoder, we cluster the actions based on their embeddings from the action encoder, after training for 50000 iterations. Below is an example of the 5 clusters trained with the role selection interval equal to 5.

Fig 2. Action clusters. The clusters of the action embeddings from the action encoder.

Each point in the figure represents an action, which is labeled by (steering dimension, throttle dimension). From the plot, we did not observe expected grouping, such as where the accelerating actions are in one cluster, the decelerating actions are in one cluster, and the steering actions are in one cluster. The actions are distributed rather uniformly. The two largest clusters, orange and purple, contain actions with very different semantics.

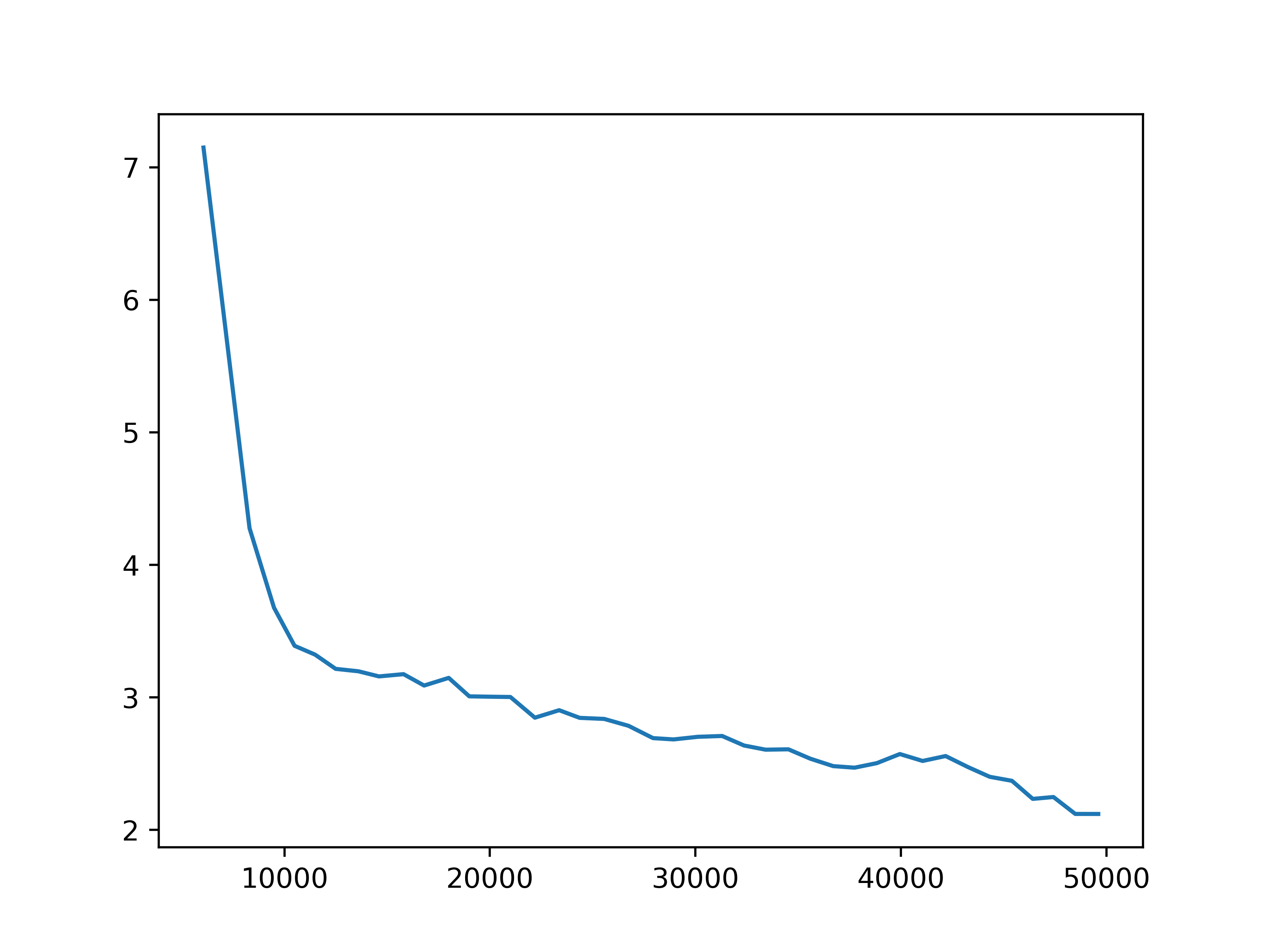

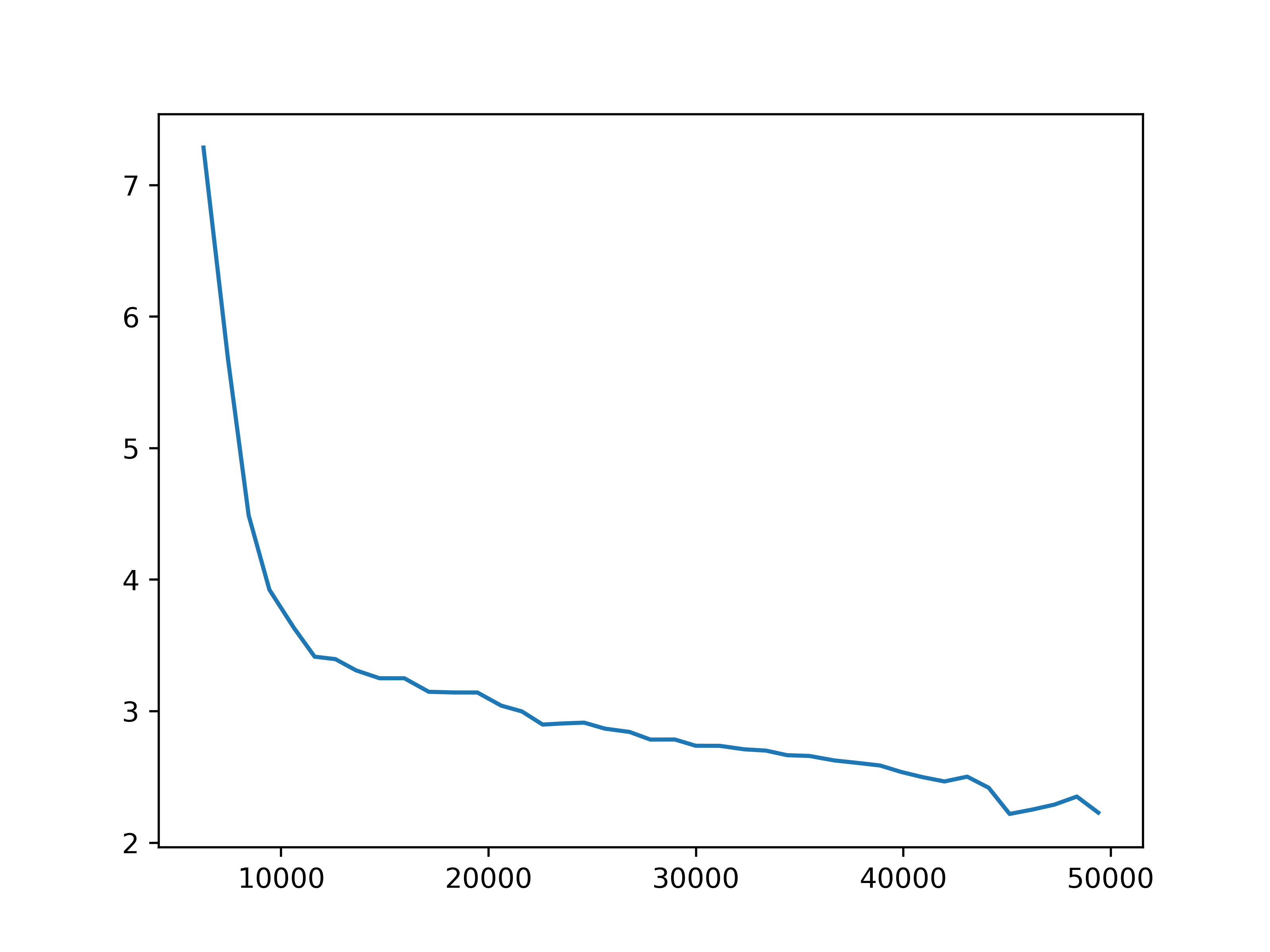

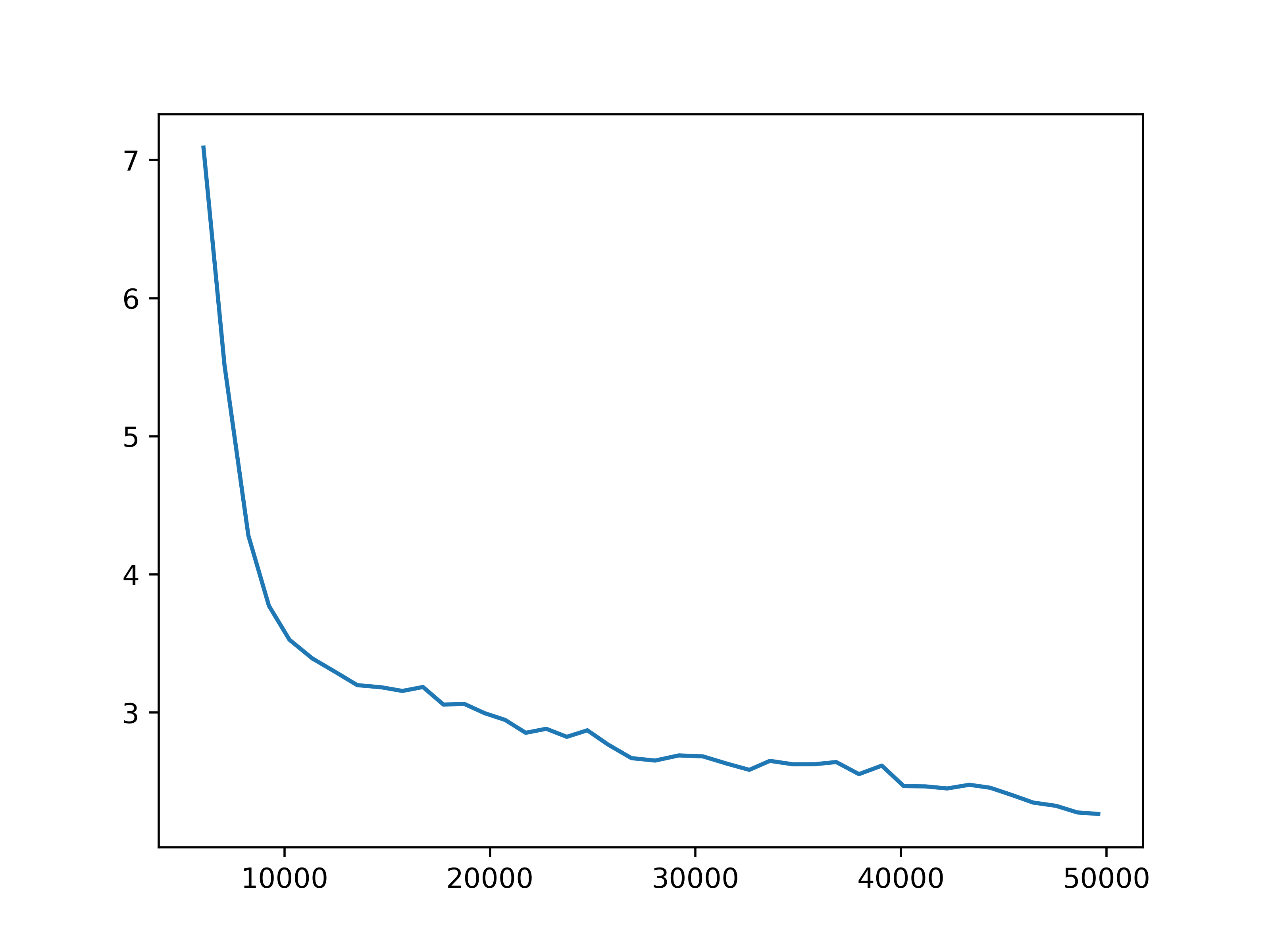

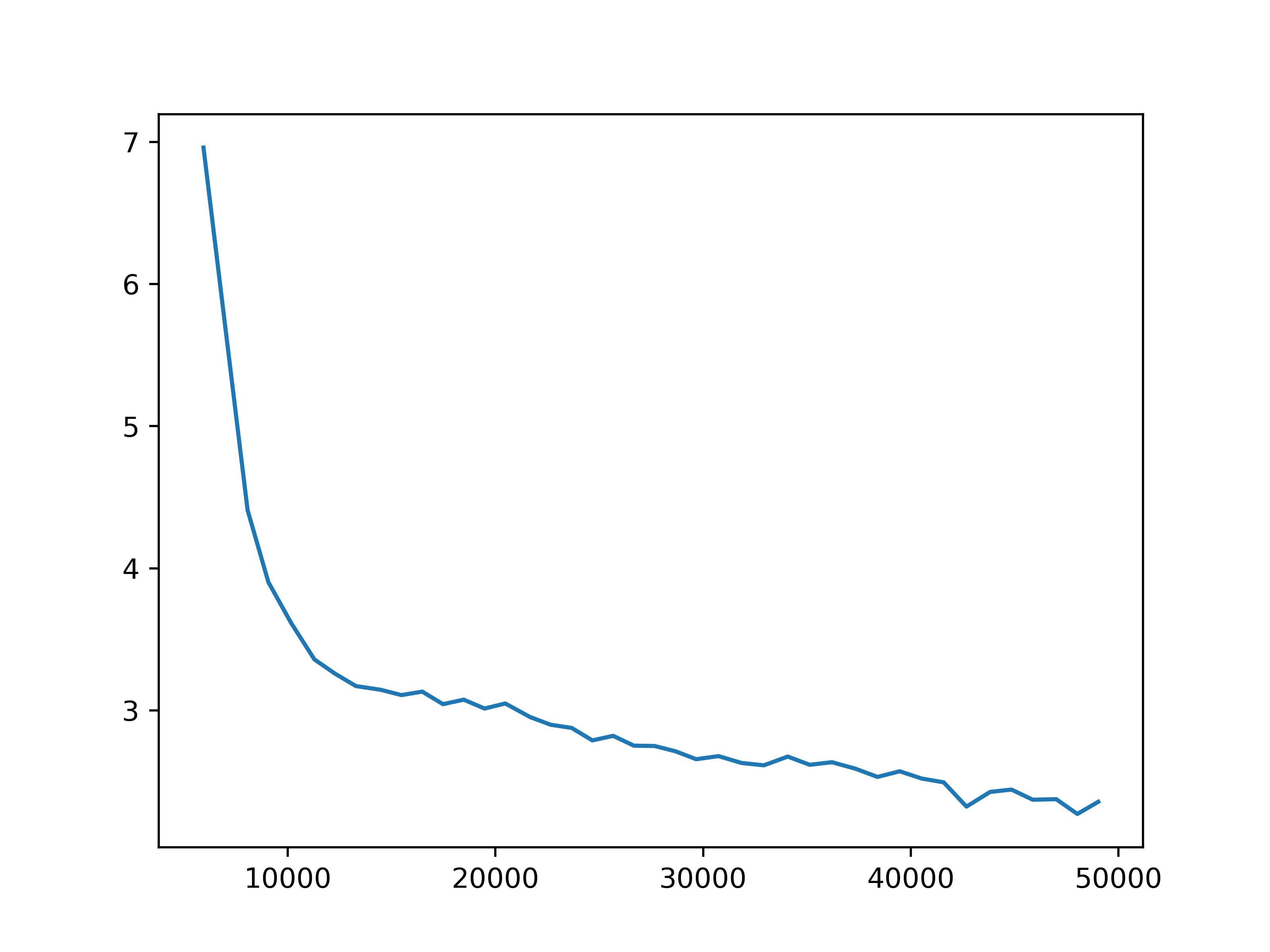

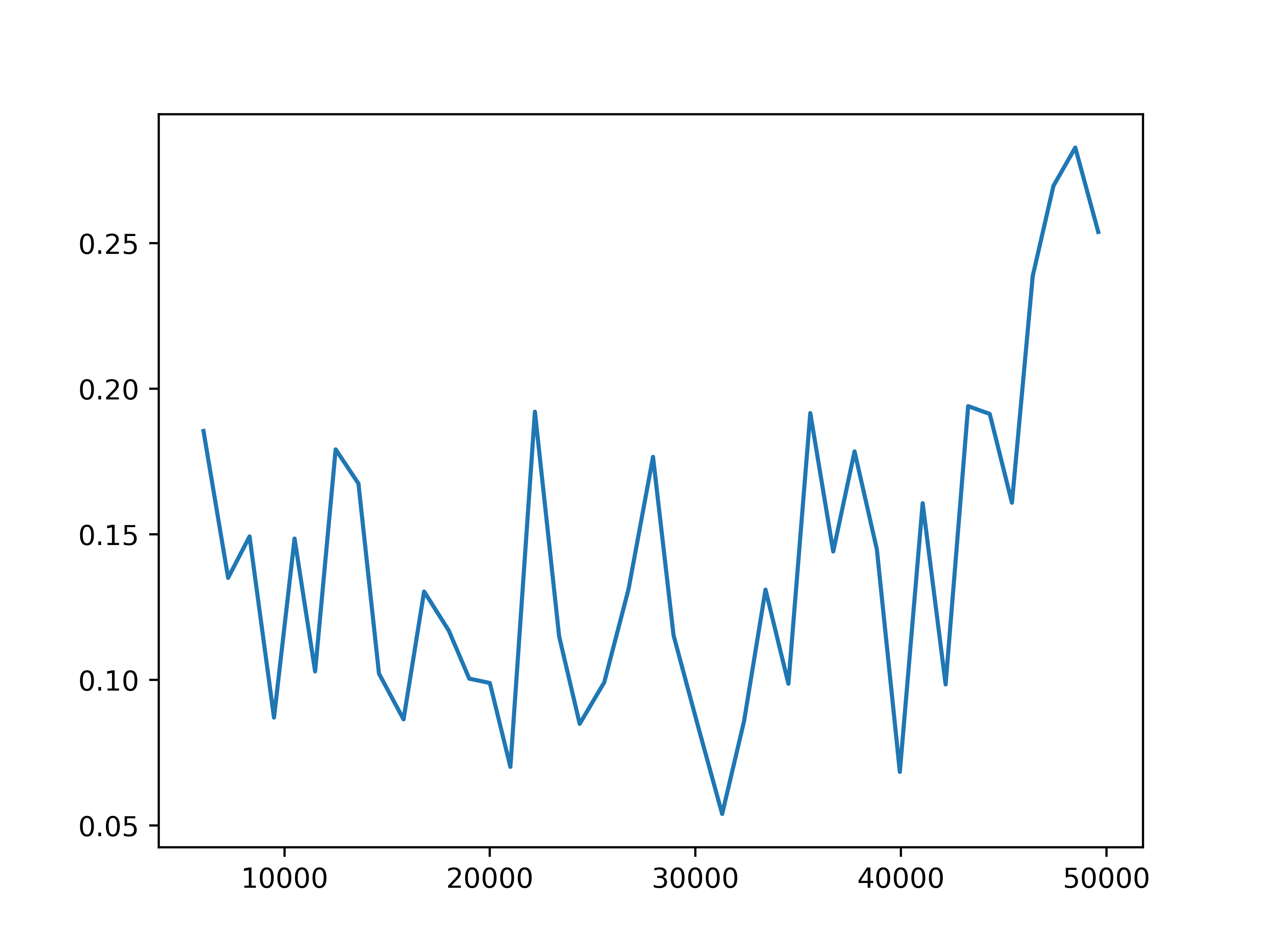

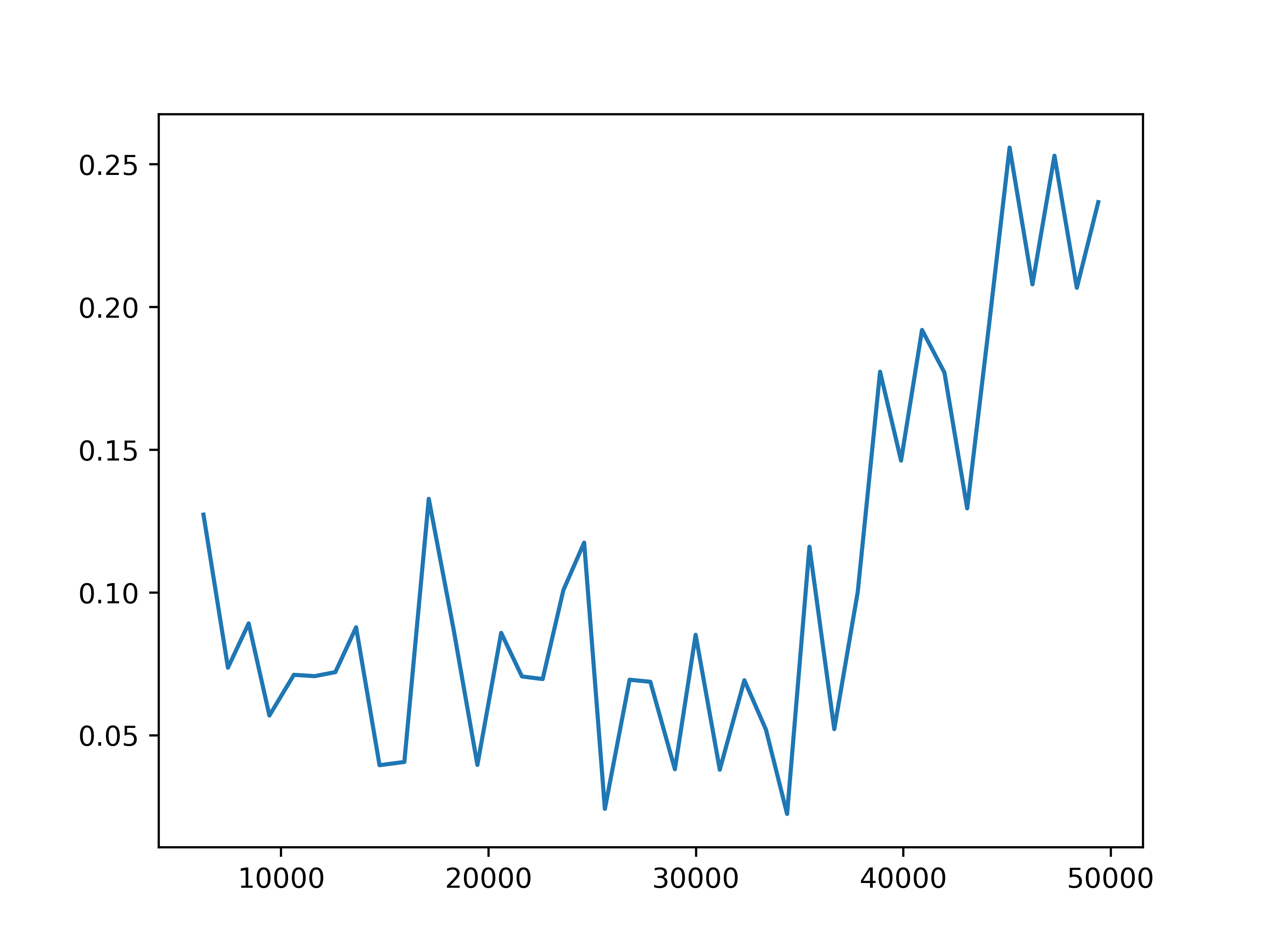

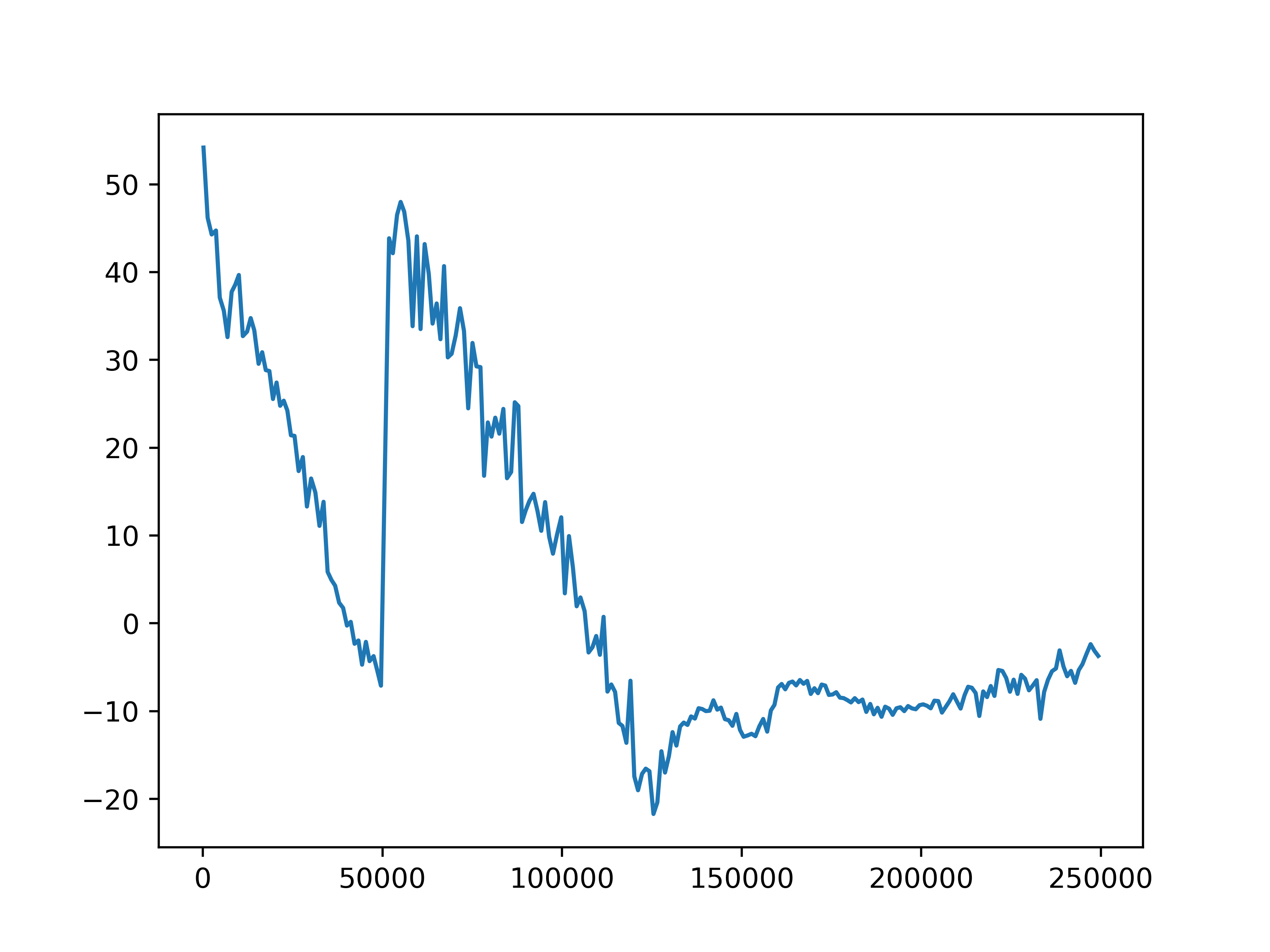

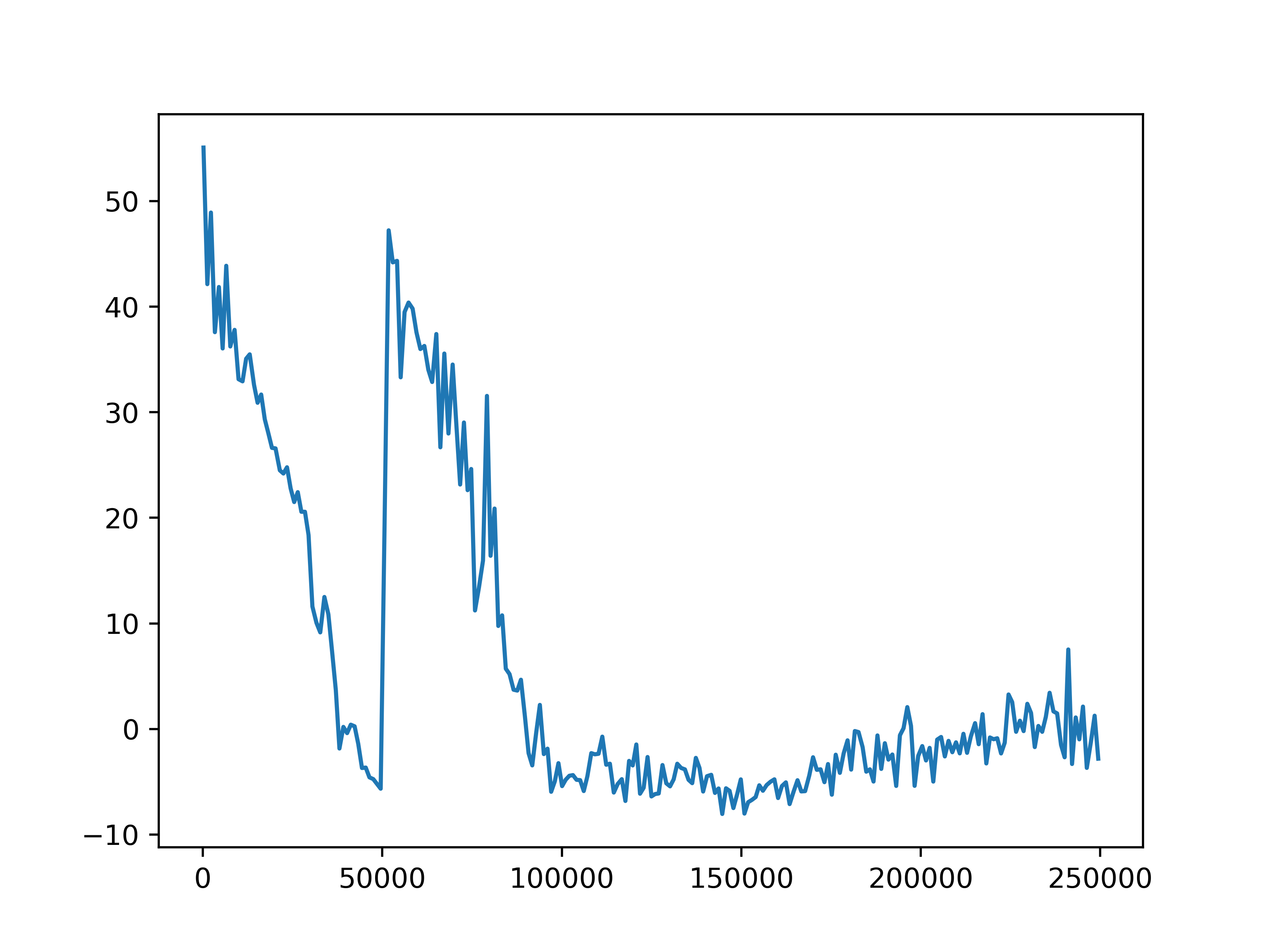

Training Trajectories: RODE

We have trained RODE under four settings, by choosing the role selection interval between 2 and 5, and the number of role clusters between 5 and 10. For each setting, some key training statistics are shown below.

| 5 roles, role interval=2 | 5 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=5 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

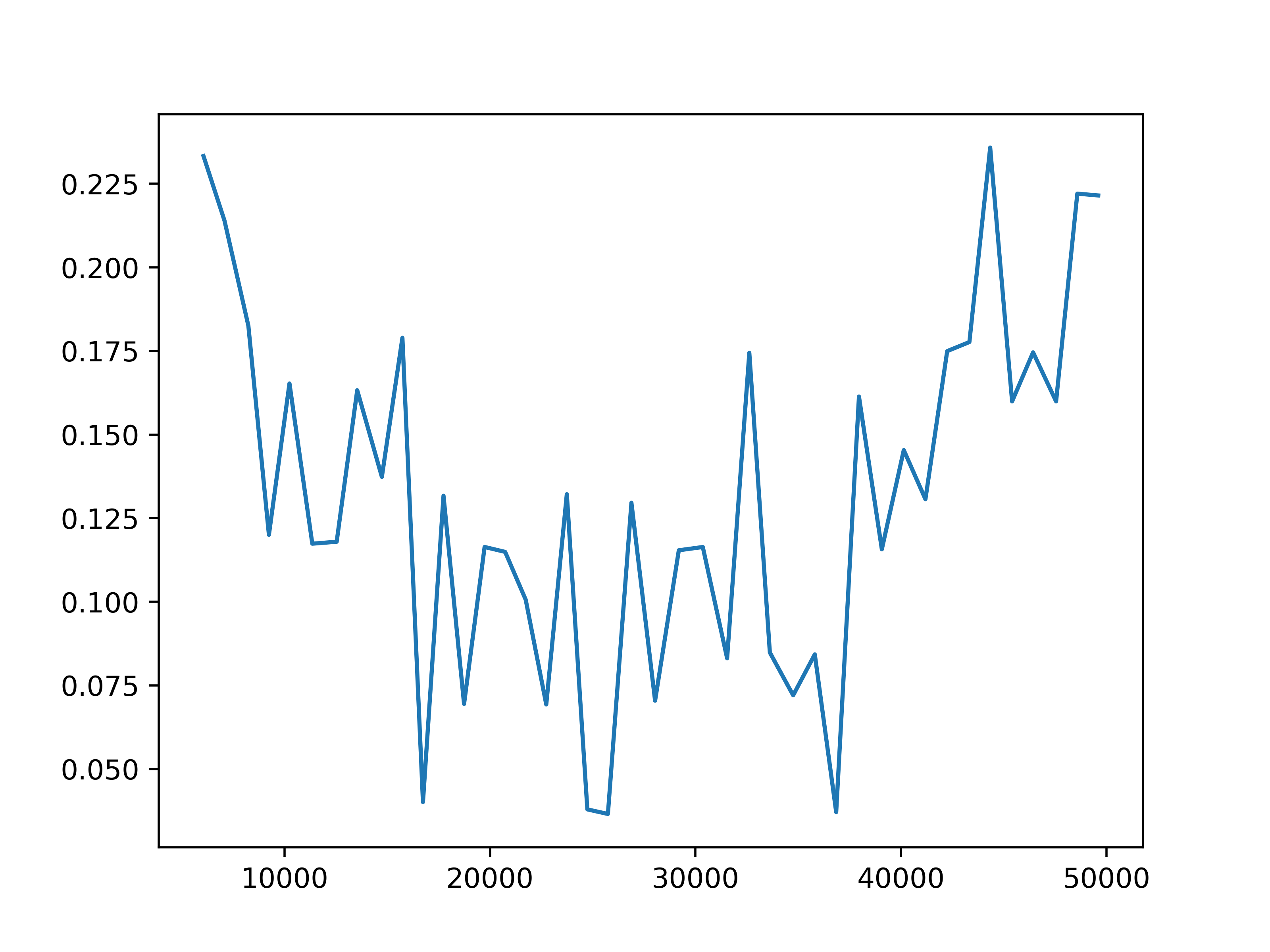

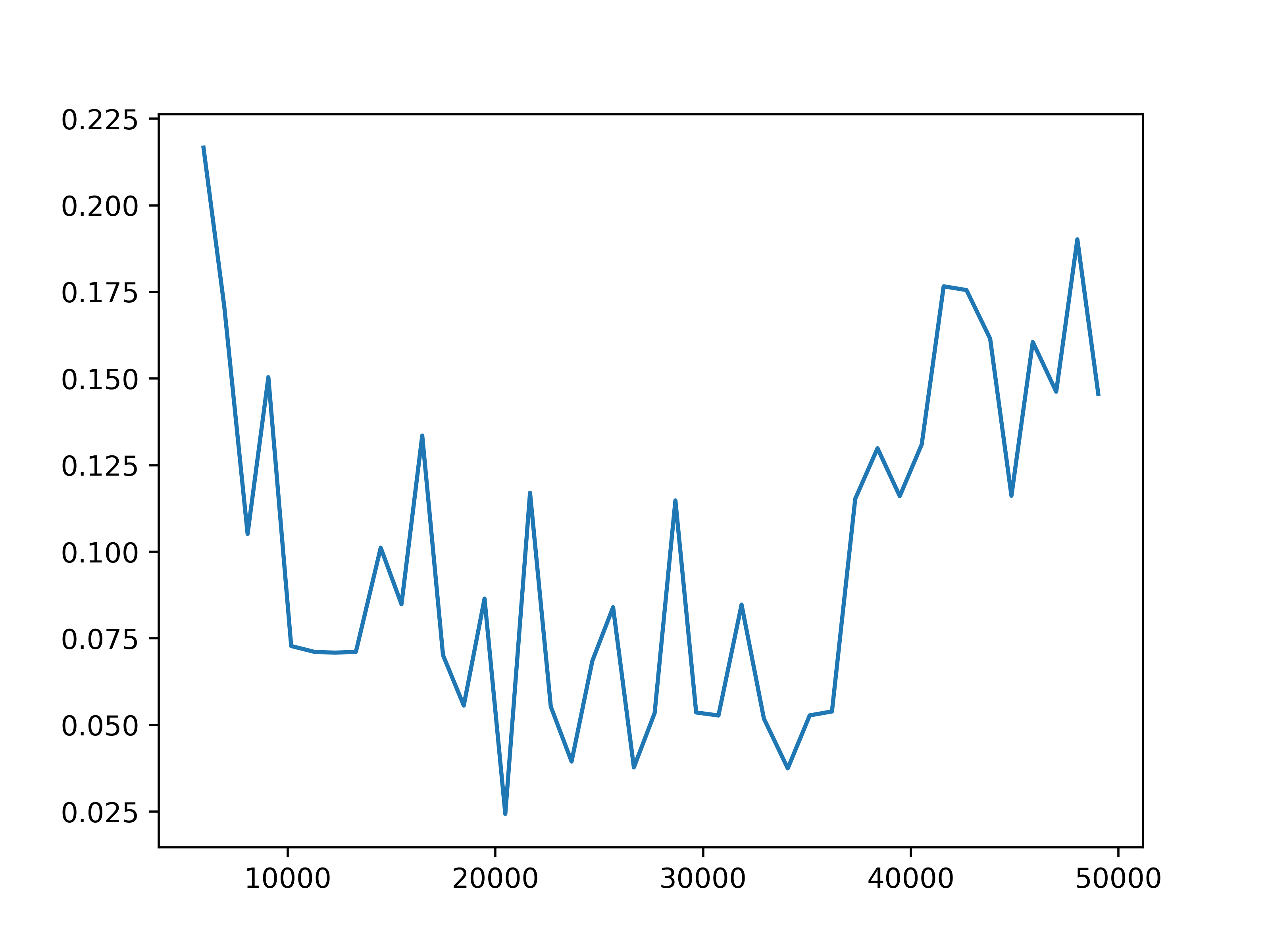

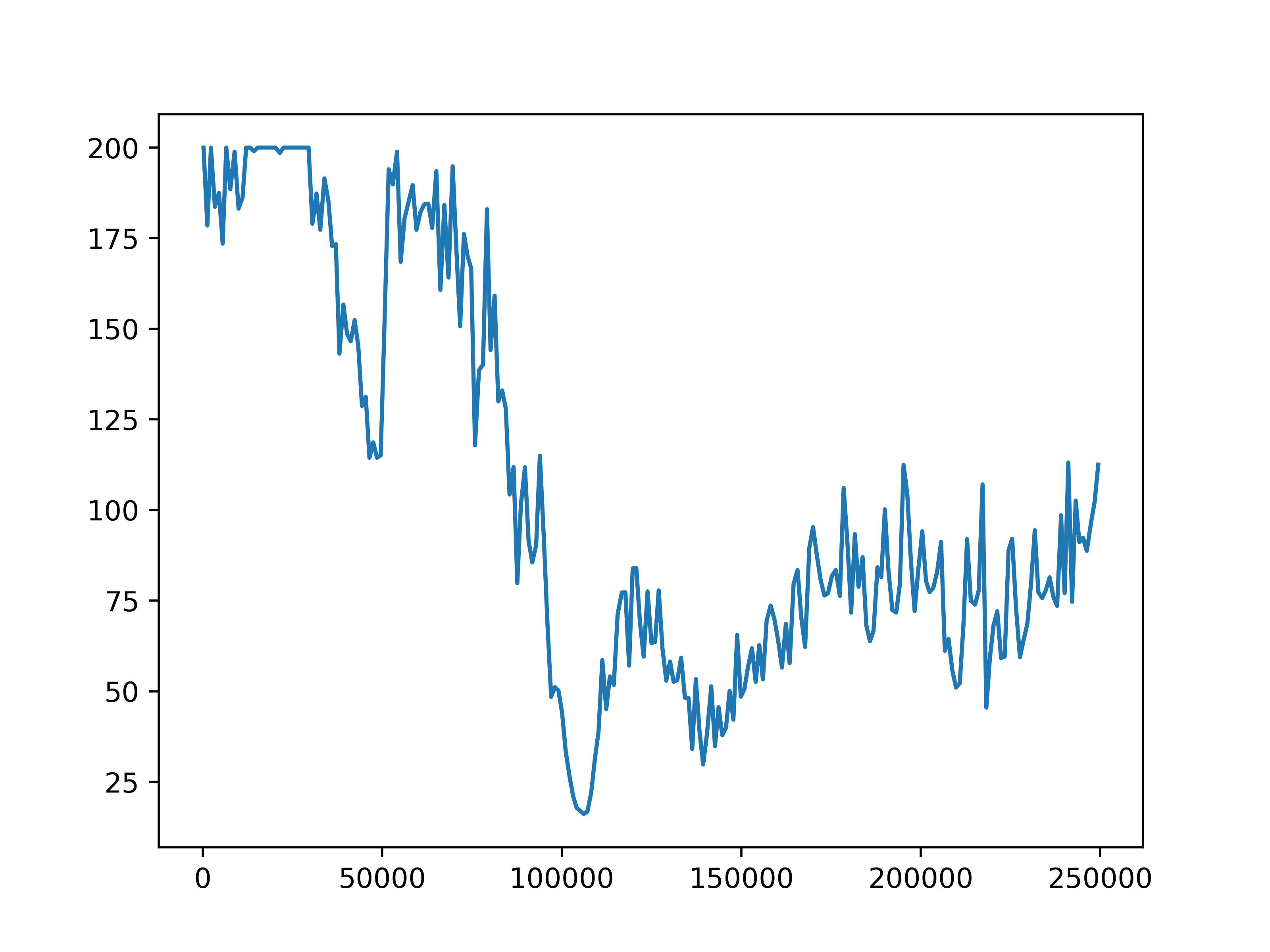

Fig 3. Observation prediction loss. The training next step observation prediction loss for each of the four settings.

| 5 roles, role interval=2 | 5 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=5 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Fig 4. Reward prediction loss. The training reward prediction loss for each of the four settings.

We observe some general patterns across the settings. While the training loss for predicting next observations keeps decreasing during the training of the action encoder, the prediction loss for rewards stops decreasing before the training for the action encoder completes. This might be due to observations being predicted for each agent, but the global reward is the sum of reward signals from all agents. Then it is more difficult for the network to learn the structure of the reward. This issue may be mitigated by changing the reward prediction objective to the concatenation of rewards from each agent, which provides more specific guidance.

| 5 roles, role interval=2 | 5 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=5 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

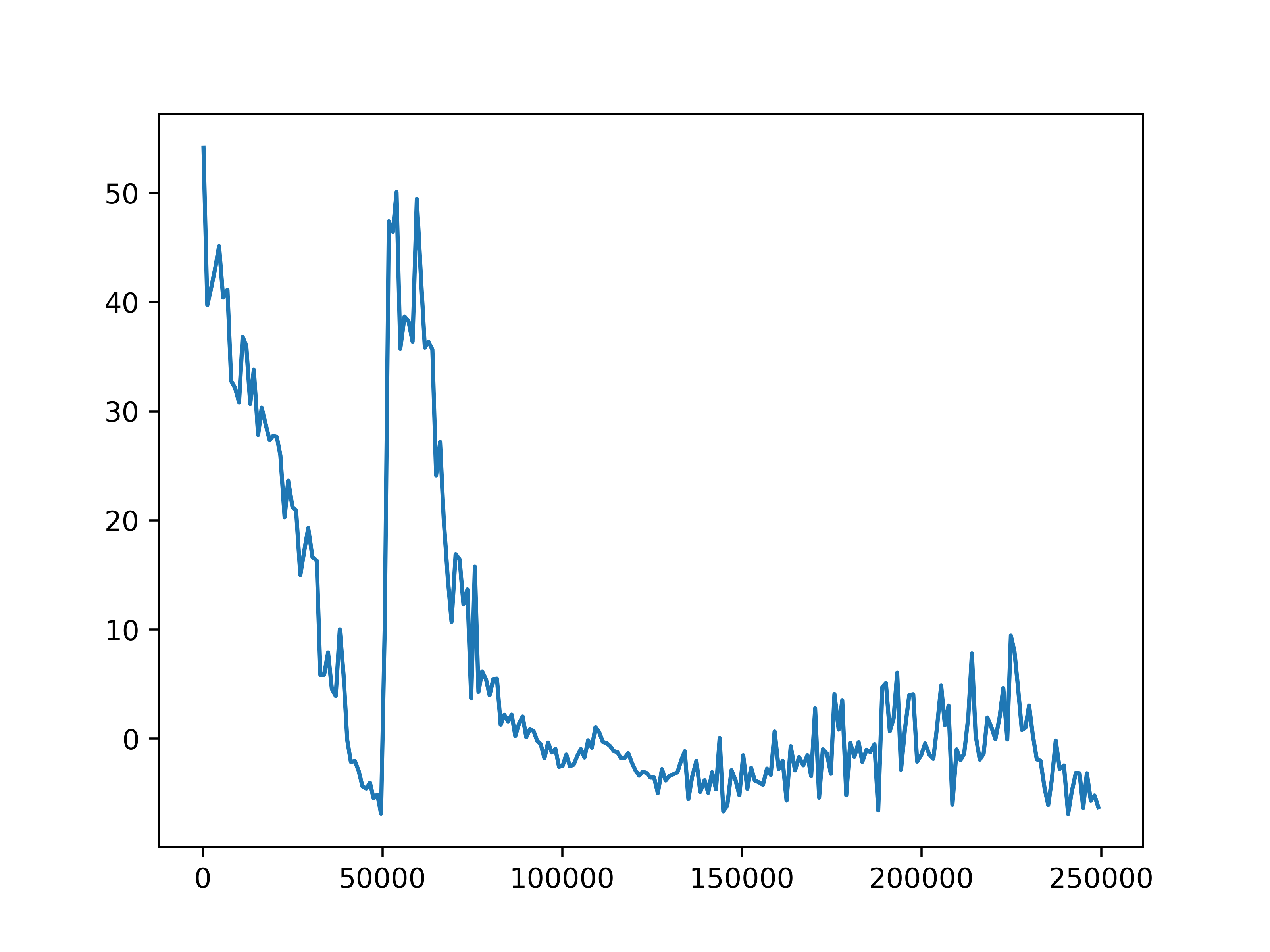

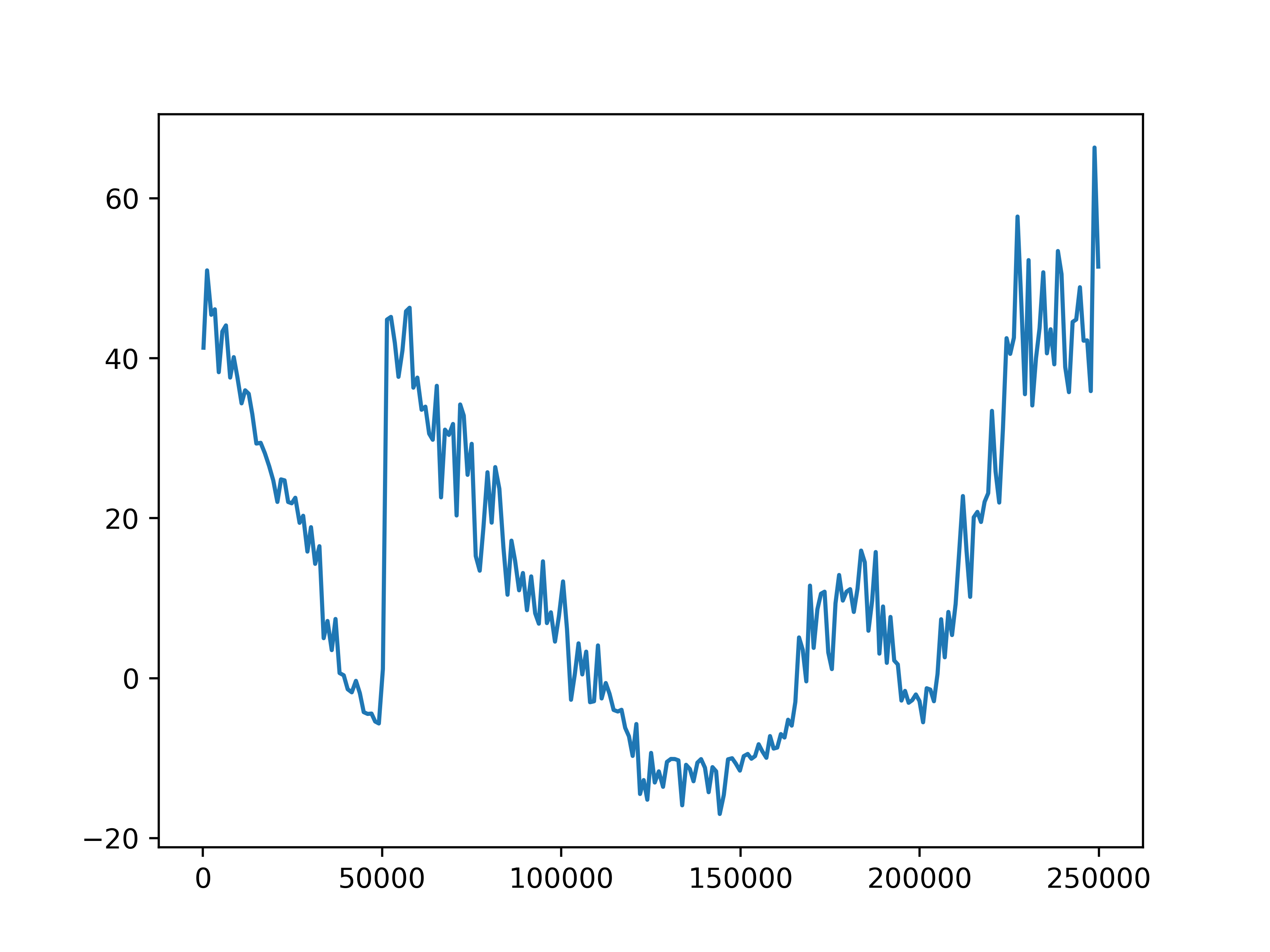

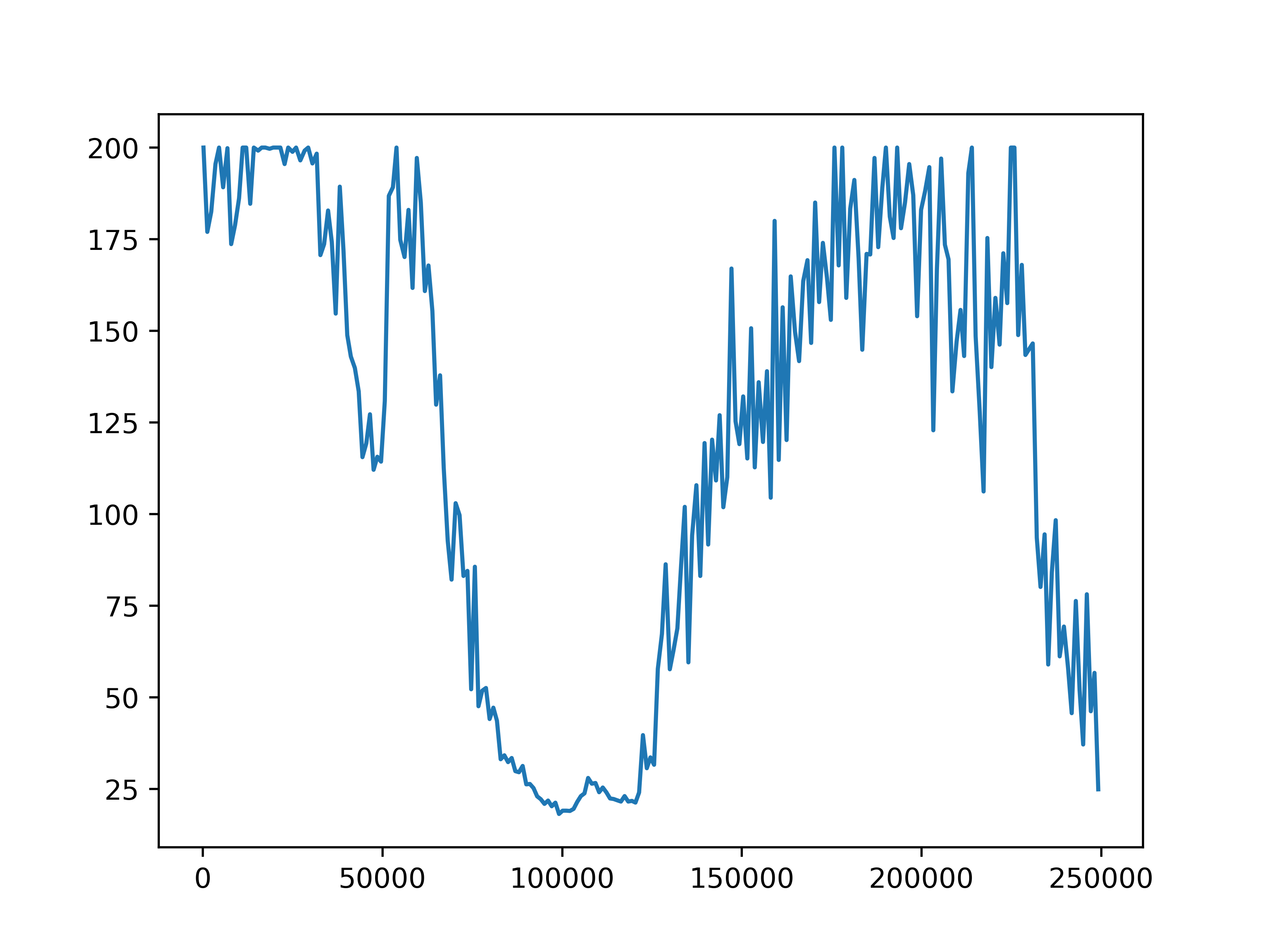

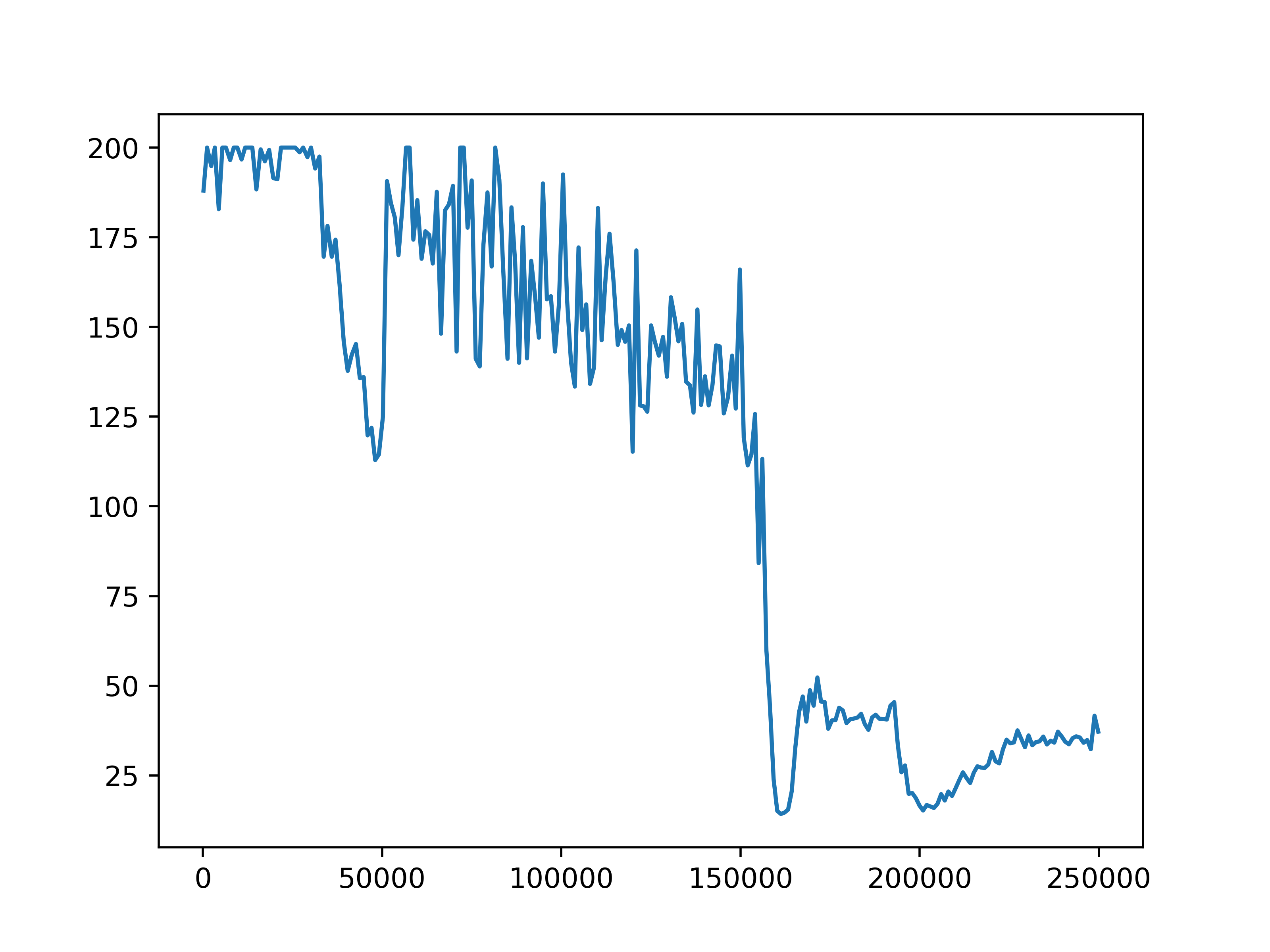

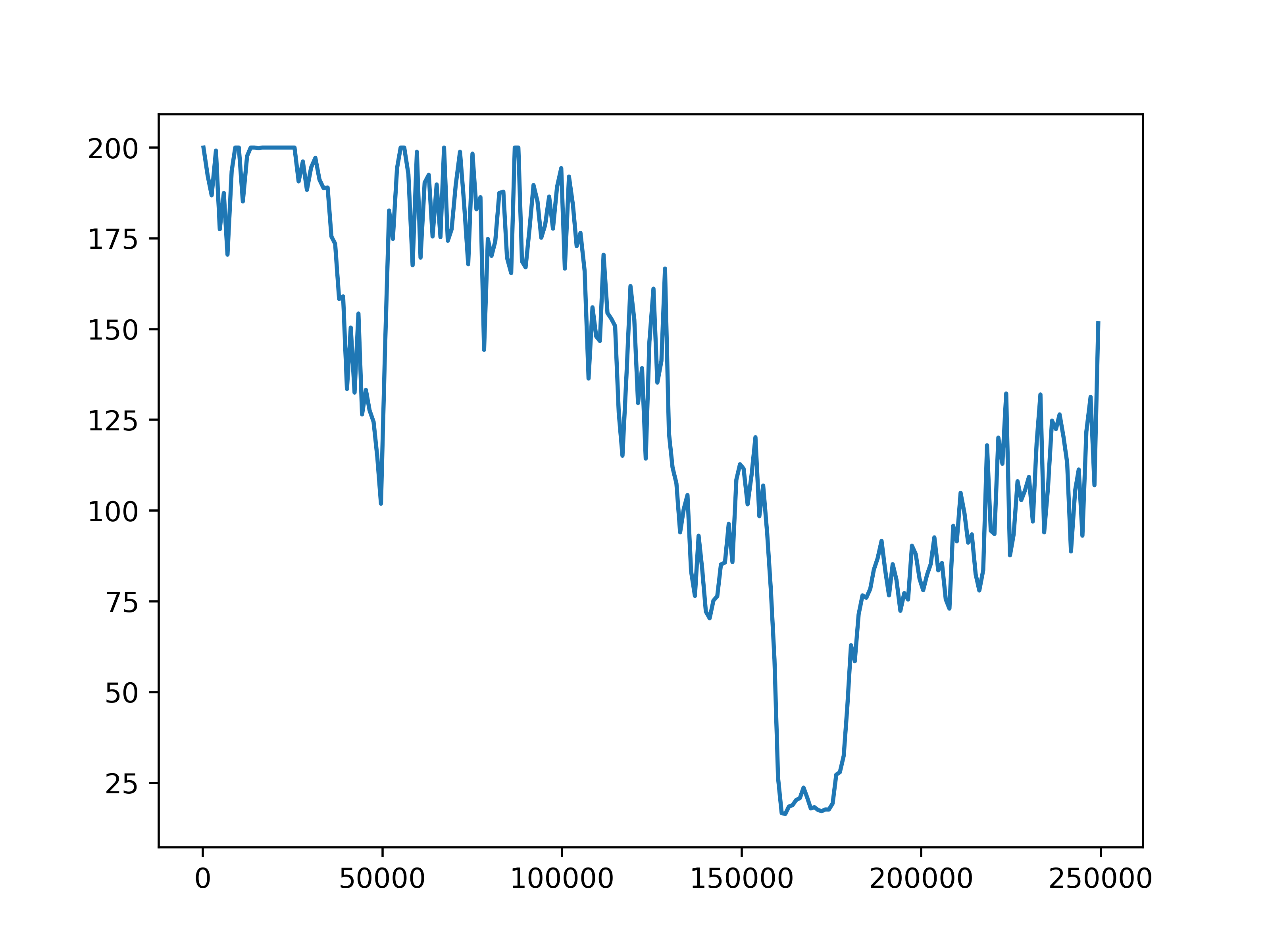

Fig 5. Average episode rewards. The average episode rewards for each of the four settings.

| 5 roles, role interval=2 | 5 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=2 | 10 roles, role interval=5 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Fig 6. Average episode length. The average episode length for each of the four settings.

The average episode return and length show our training has not been successful. In general, agents fall into two failure cases. One is that the episode length is short but the reward is high, which means that agents are driving with high speed but not safely. The second case is that the episode length is longer but the reward is low, such as in the setting with 10 role clusters and 2 step role selection interval, which means the agents are barely making progress towards the destination. We do observe an upward trend in reward in the setting with 10 role clusters and 2 step role selection interval. However, due to computation limits, we could not train the model for long enough to observe significant progress.

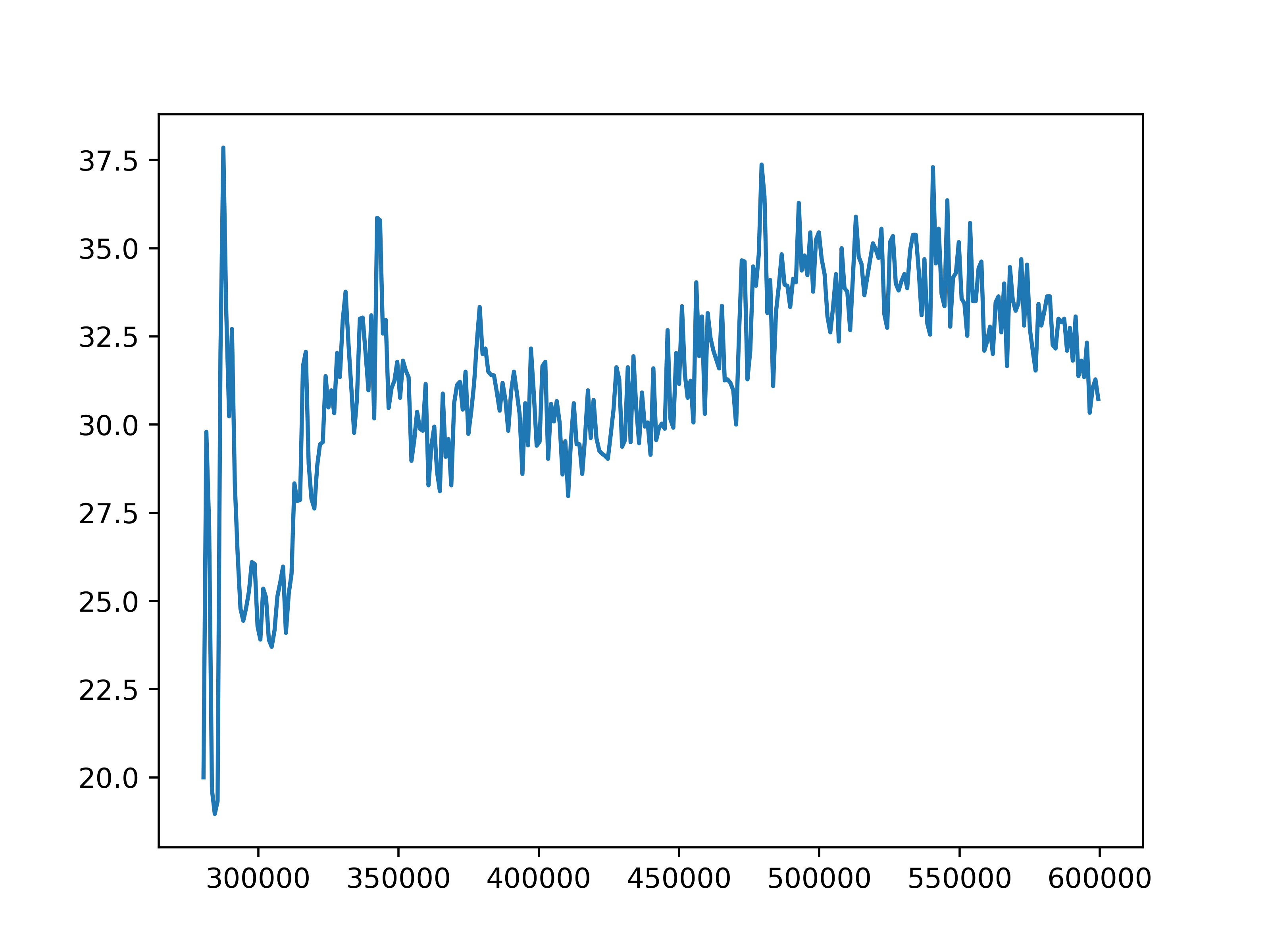

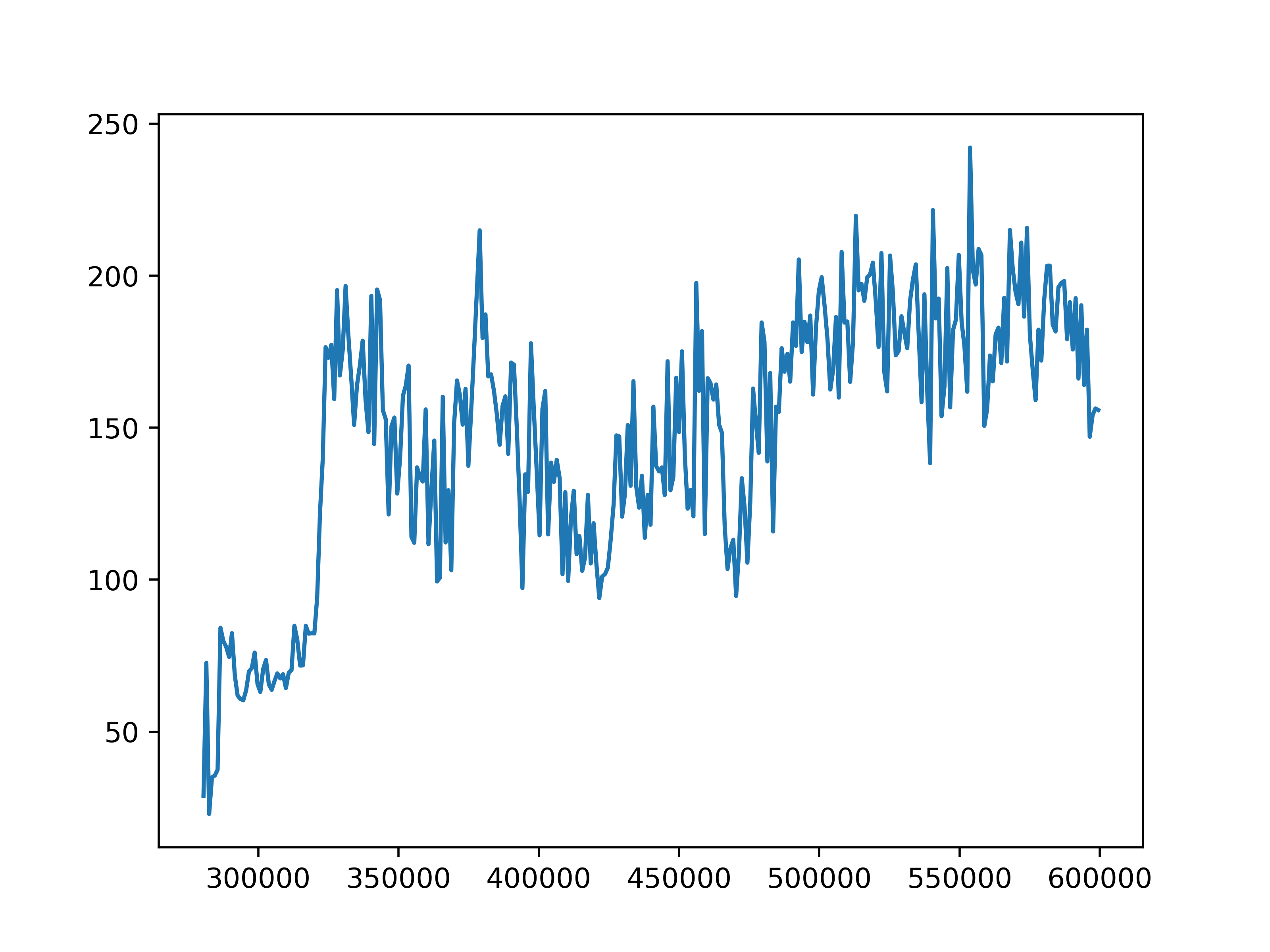

Training Trajectories: QMIX

As a baseline, we trained QMIX on the same environment settings for 600000 iterations with global reward and termination condition. The training trajectories for average episode length and rewards are shown below. In this case, the QMIX model falls into a similar situation where the agents drive with high speed but terminate quickly.

| episode length | episode reward |

|---|---|

|

|

Fig 7. Training statistics for QMIX. The average episode length (left) and reward for (right).

Training with relaxed termination conditions

In previous training, we used a global termination status, where the episode ends when either of the agents terminates. We attempted to relax this condition by repawning agents when an agent terminates and let the episode continue. However, while we try to rely on the auto respawning mechanism of Metadrive by setting allow_respawn to True, sometimes the agents do not respawn. We did not find out the specific reason for this issue. Therefore, we could not pursue further into this direction.

Discussion

Roles under the driving scenario

Since the multi-agent driving scenario requires a high level of coordination with the optimal strategy potentially changing at each timestep, one hypothesis we make regarding the unsatisfactory performance of RODE is that the enforcement of the idea of roles is too restrictive for cooperative behavior in driving scenarios. Since our results indicate that the group performance increases as we decrease the role switching interval (i.e. to switch roles more often), one natural reasoning is that roles are simply not applicable in driving scenarios. While the RODE algorithm demonstrates state-of-the-art performance in the widely-used benchmark Starcraft task[13], it is likely due to the fact that agents in Starcraft possess various capabilities which enable more clear-cut definition of roles.

Future directions

For our experiments, each model requires around 20 hours to train under CPU. Due to computational and time constraints, we were unable to perform a comprehensive search over the parameter space. Further work in parameter tuning is required in order to better demonstrate the results.

Relevant papers:

[1] Cao, Y., Yu, W., Ren, W., and Chen, G. An overview of recent progress in the study of distributed multi-agent coordination. IEEE Transactions on Industrial informatics, 9(1):427–438, 2012.

[2] Zhang, C. and Lesser, V. Coordinated multi-agent reinforcement learning in networked distributed pomdps. In Twenty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2011.

[3] Nowe, A., Vrancx, P., and De Hauwere, Y.-M. Game theory and multi-agent reinforcement learning. In ReinforcementLearning, pp. 441–470. Springer, 2012.

[4] Peng, Z., Li, Q., Hui, K. M., Liu, C., & Zhou, B. (2021). Learning to simulate self-driven particles system with coordinated policy optimization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, 10784-10797.

[5] Wang, T., Gupta, T., Mahajan, A., Peng, B., Whiteson, S., & Zhang, C. (2020). Rode: Learning roles to decompose multi-agent tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.01523.

[6] Tonghan Wang, Heng Dong, Victor Lesser, and Chongjie Zhang. Roma: Multi-agent reinforcement learning with emergent roles. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2020c.

[7] Rashid, T., Samvelyan, M., Schroeder, C., Farquhar, G., Foerster, J., and Whiteson, S. QMIX: Monotonic value function factorisation for deep multi-agent reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 80 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 4295–4304, Stockholmsmssan, Stockholm Sweden, 10–15 Jul 2018.

[8] Smith, A. (1937). The wealth of nations [1776] (Vol. 11937). na.

[9] Tomasello, M. (2009). Why we cooperate. MIT press.

[10] Wang, J., Ren, Z., Liu, T., Yu, Y., & Zhang, C. (2020). Qplex: Duplex dueling multi-agent q-learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.01062.

[11] Sunehag, P., Lever, G., Gruslys, A., Czarnecki, W. M., Zambaldi, V., Jaderberg, M., … & Graepel, T. (2017). Value-decomposition networks for cooperative multi-agent learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05296.

[12] Oliehoek, F. A., & Amato, C. (2016). A concise introduction to decentralized POMDPs. Springer.

[13] Samvelyan, M., Rashid, T., De Witt, C. S., Farquhar, G., Nardelli, N., Rudner, T. G., … & Whiteson, S. (2019). The starcraft multi-agent challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.04043.