The Decision Transformer: A Conditional Sequential Model in Reinforcement Learning

The development of Transformers in machine learning has allowed the possibilities of high-dimensional distribution models of semantic concepts at scale. However, the applications of transformers have mostly been limited to language generalization and image generation. Therefore, this article introduces the Decision Transformer (DT) [42], an offline reinforcement learning (RL) method. The DT uses conditional sequence modelling which allows it to leverage the simplicity and scalability of the Transformer. In the DT, an autoregressive generative model is conditioned on the return, previous states and actions. This enables the DT to obtain future actions with the desired return. Through comprehensive experiments using the OpenAI Gym of the DT against state-of-the-art model-free offline RL baselines, the DT remains extremely competitive and outperforms the other models.

- Blog Presentation Video

- Introduction

- Related Works

- Decision Transformer

- Experiments and Discussions

- Conclusion

- Code Repository

- References

Blog Presentation Video

Note: The recording is done on Zoom thus, the video demos appear laggy.

Introduction

The transformer is a sequence transduction model that utilises the attention mechanism where dependencies can be modeled regardless of their length between the input and output sequences [1]. A major advantage of the transformer is that it is able to process the whole input simultaneously, enabling parallization to improve efficacy. Within the fields of natural language processing (NLP) and computer vision (CV), a transformer is much more efficient than its counterparts where it achieves state-of-the-art (SOTA) performances. Hence, the Decision Transformer (DT) aims to leverage the proficiencies of the transformer and extend its applications to the areas of reinforcement learning.

In the DT, it is trained with the input of state, action and return-to-go (sum of future rewards) to create a generative trajectory model that maximises the expected return. Utilising this architecture does not require us bootstrap or discount future rewards. This is greatly beneficial since the “deadly triad” [2] can be avoided where the value function suffers from instabilities as well as short-sightness of the model respectively. Furthermore, through the self-attention of a transformer, credit can be assigned directly to update the weights compared to Bellman backups where the parameterization of the model is slow and can be affected by “distractor” signals (unrelated “distractor” task containing rewards that affects the model’s decision making). Last but not least, the DT is modeled as an offline reinforcement learning problem, meaning that the agent does not interact with the environment and only utilizes data collected from other agents or human demonstrations [4]. With offline RL, the DT learns maximally effective policies despite only using limited data. Additionally, the model reduce the use of policy sampling due to the autoregressive generative nature of the model.

Hence, with the aforementioned benefits of the transformer, I expect the DT to train efficiently, generalize reliably and optimize accurately in a reinforcement learning setting.

Related Works

Offline RL

Offline RL often faces issues of distributional shifts. Therefore, works to circumvent this issue includes constraining the policy action space ([10], [11], [12]), integrating value pessimism ([10], [13]) and integrating pessimism into learned dynamic models ([14], [15]). Adding a dynamic model into model-free methods typically improve their performances. Hence, it makes sense to take it into consideration since the DT is compared to other model-free methods.

On the other hand, likelihood-based approaches ([16], [17], [18], [19]) and mutual information maximization ([20], [21], [22]) has also been used to learn task-agnostic/self-modeling skills. Even though the DT utilizes a simpler sequence modeling objective and rewards for conditional generation of behaviors, it still resembles likelihood-based approaches where iterative Bellman updates are not used.

Reinforcement Supervised Learning

“Upside-down” reinforcement learning ([23], [24], [25]), a form of reinforcement supervised learning, bears resemblance to the DT since it seeks to model behaviors with a supervised loss conditioned on the target return. This allows us to use behavior modeling without requiring the reward which is known to have good scaling properties [26] and is similar to NLP [9] and CV [27]. However, in the DT, it utilizes sequential learning instead of supervised learning.

Recently, the Trajectory Transformer (TT) [28] has also been developed which is similar to the DT but includes state prediction, return prediction and discretization that integrates model-based features. The positive results in both the TT and DT further reiterates the fact that sequence modeling has huge potential in RL and its applications should be further explored.

Credit Assignment

Several research has been written to improve credit assignment through state-association, where an architecture decomposes the reward function to depict the most salient states that would comprise the most credit ([29], [30], [31]). With the learned reward function, the algorithm updates the actor-critic reward to enable signal propagation across a long horizon. Furthermore, state-association has shown improved performance under delayed reward settings ([3], [32], [33], [34]). State-association is present in the DT in the form of the transformer architecture where a reward function or a critic is not required to be explicitly learned.

Transformer and Attention Models

The application of the transformer model to machine learning subfields such as NLP ([36], [9]) and CV ([37], [38]) have shown great success. Nonetheless, its application has been relatively underexplored in reinforcement learning due to a high-variance setting.

Recent research has displayed that transformer augmentation coupled with relational reasoning improves performance in combinatorial environments [39]. Additionally, iterative self-attention leads to an improvement in episodic memory usage for RL agents [40]. Furthermore, there is also work to tackle the stabilization of transformers when there is higher variance in training [41].

These features combined emphasises the importance of exploring transformers in RL.

Decision Transformer

Leveraging Offline RL

In the DT, it considers the use of offline RL to learn policies from fixed limited datasets that consists of trajectory rollouts of arbitrary policies. This is possible due to the autoregressive and generative nature of the model, where policy sampling can be reduced to produce pristine behavior from fixed, limited experience.

The DT evaluates the Offline RL section of the model using a Markov Decision Process (MDP).

Offline RL MDP Notations

The MDP is described using tuple \((S, A, P, R)\) and is broken down as follows:

- states \(s \in S\)

- actions \(a \in A\)

- transition dynamics \(P(s' \mid s, a)\)

- reward function \(r = R(s, a)\)

- state, action and reward at timestep t: \(s_t, a_t, r_t = R(s_t, a_t)\)

- trajectory \(\tau = (s_0, a_0, r_0, s_1, a_1, r_1, ..., s_T, a_T, r_T)\)

- return of trajectory at timestep \(t\): \(R_t = \sum_{t'=t}^{T} r_{t'}\)

Transformer Architecture

A transformer is one of the recent pioneering developments in modeling sequential data efficiently. It leverages stacked self-attention layers with residual connections. A self- attention layer receives \(n\) embeddings \(\{x_i\}^{n}_{i=1}\) corresponding to unique input tokens, and outputs n embeddings \(\{z_i\}^{n}_{i=1}\), preserving the input dimensions. The \(i\)-th token is mapped via linear transformations to a key \(k_i\), query \(q_i\), and value \(v_i\). The \(i\)-th output of the self-attention layer is given by weighting the values \(v_j\) by the normalized dot product between the query \(q_i\) and other keys \(k_j\). The output \(z_i\) is modeled as follows.

\(z_i = \sum_{j=1}^{n}softmax(\{<q_i, k_{j'}>\}_{j'=1}^{n})_j \cdot v_j\)

Decision Transformer Architecture

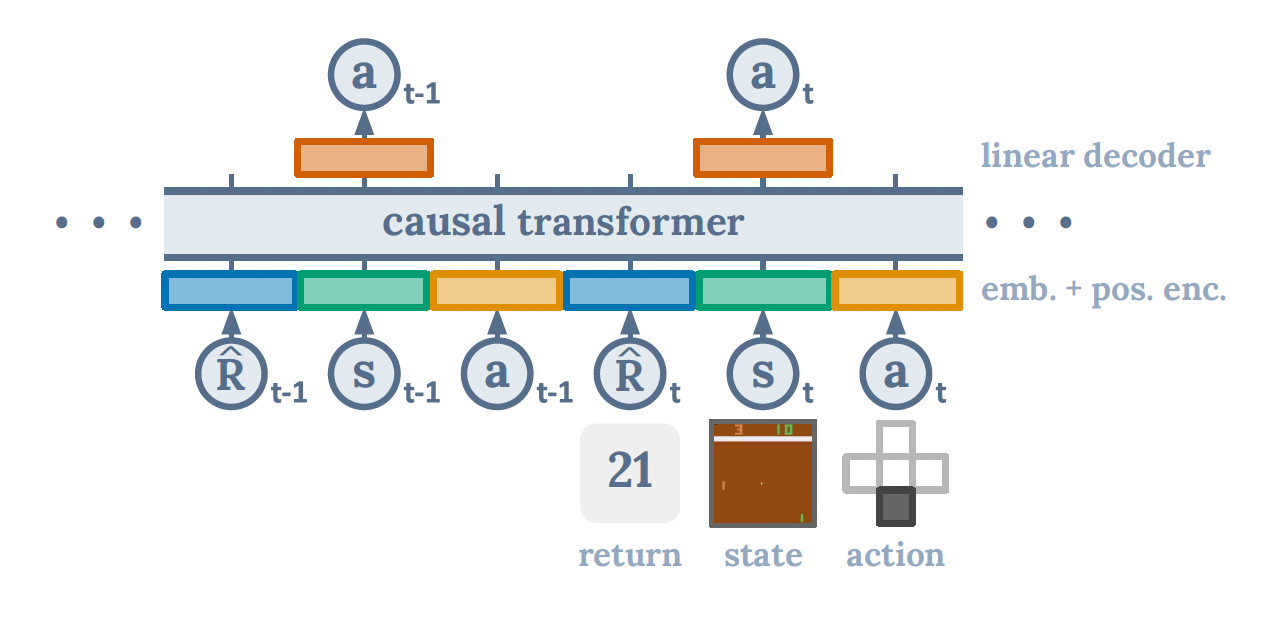

In order to generate actions based on future desired returns instead of past rewards, the DT replace the reward function with “returns-to-go” \((\hat R_t = \sum_{t = t'}^{T} r_{t'})\). Thus, our trajectory \(\tau\) is as follows:

\[(\hat R_1, s_1, a_1, \hat R_2, s_2, a_2, ..., \hat R_T, s_T, a_T)\]The last K timesteps are fed into the DT i.e. 3K tokens (1K for each modality: return-to-go, state and action). In each of the modalities, the DT learns a linear layer to project raw inputs to the embedding dimension, followed by layer normalization. Environments using visual inputs learn a convolutional encoder instead of a linear layer. Furthermore, an embedding for each timestep is learned and added to each token. Lastly, it utilizes GPT [9] to process the tokens.

The DT sample minibatches of sequence length K from the dataset of offline trajectories. Cross-entropy loss and mean-squared error is used to evaluate the prediction head corresponding to the input token \(s_t\) for discrete and continuous actions respectively. Finally, the losses are averaged for each timestep.

*Figure 1. Decision Transformer Architecture.

Experiments and Discussions

I evaluate the performance of the Decision Transformer against other state-of-the-art model-free methods using the OpenAI Gym [43]. The hyperparameters used are tuned using a linear scan and suggested by the authors as follows.

- Batch Size = 64

- Dropout = 0.1

- Learning Rate = 0.0001

- Weight Decay = 0.0001

- Gradient Norm Clipping = 0.25

- Return-to-go conditioning (HalfCheetah) = 6000

- Return-to-go conditioning (Hopper) = 3600

- Return-to-go conditioning (Walker) = 5000

The dataset used in the experiments is the “Medium-Replay” dataset since the authors use it as their primary comparison. It is also the replay buffer of an agent trained to the performance of a medium policy.

The model-free methods that will be compared against include CQL [5], BEAR [6], BRAC [7], and AWR [8]. The values are reported from the Decision Transformer paper. The results of the expected returns are as follows. They are normalized so that a return of 100 is equivalent to an expert policy.

| Dataset | Environment | DT (my run) | DT (authors’ run) | CQL | BEAR | BRAC-v | AWR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-Replay | HalfCheetah | 45.0 | 36.6 | 46.2 | 38.6 | 47.7 | 40.3 |

| Medium-Replay | Hopper | 27.3 | 82.7 | 48.6 | 33.7 | 0.6 | 28.4 |

| Medium-Replay | Walker | 28.7 | 66.6 | 26.7 | 19.2 | 0.9 | 15.5 |

*Table 1. Performance of the Decision Transformer against other SOTA model-free methods using the OpenAI Gym

As shown in the table above, due to limited computational power and larger datasets of Hopper and Walker, I am unable achieve similar performance results. On the other hand, my result achieved from HalfCheetah (45.0) is competitive against the SOTA BRAC-v (47.7) and better than the authors’ result of 36.6.

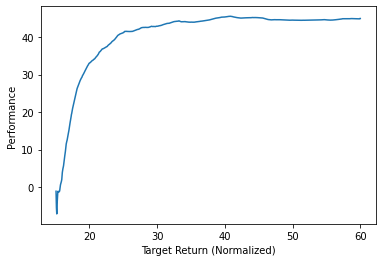

*Figure 2. HalfCheetah’s Performance vs. Target Return.

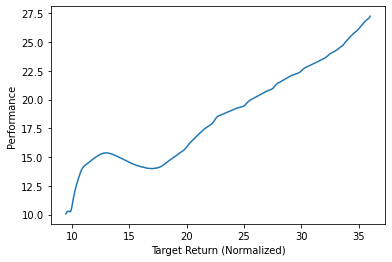

*Figure 3. Hopper’s Performance vs. Target Return.

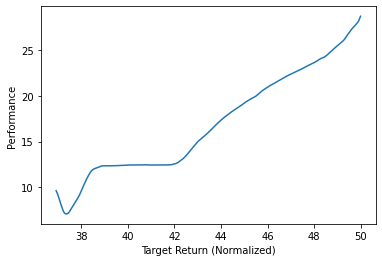

*Figure 4. Walker’s Performance vs. Target Return.

In the figures above, we observe the average sampled return accumulated by the agent over the course of the evaluation episode (Performance) for varying values of target return.

As observed, for both the Walker and Hopper, the performance is still increasing peaking at around 28.7 and 27.3 respectively. I believe that with more computing power, I will be able to achieve much higher performances and reproduce the author’s results.

Furthermore, as seen in the HalfCheetah plot, the increase in performance has plateaued and peaked at around 45.0 meaning that it is already state-of-the-art.

Video Demos of HalfCheetah, Hopper and Walker

HalfCheetah

Hopper

Walker

Since I achieve SOTA performance when training in the HalfCheetah environment, we observe that the HalfCheetah demo is fully functional and can run at ease.

On the other hand, since the Hopper and Walker is unable to achieve SOTA, we observe that the agent fails to function after a period of time.

Conclusion

I explore the Decision Transformer where ideas from both reinforcement learning and sequence modeling are combined. Additionally, there has been several areas of related works that contributes to the DT development including offline RL, reinforcement supervised learning, credit assignment, transformers and attention models. By leveraging offline RL in the DT, one key advantage is that it is able to learn from fixed limited datasets which is very useful due to the high costs and difficulties in obtaining large reliable datasets. In my experiments on the OpenAI Gym, I have proven that the DT remains extremely competitive and outperforms some model-free methods. With further training and more computational power, I believe that the DT will definitely outperform most of the other model-free methods as shown from the authors’ results. This showcases the immense potential and capabilities of Transformer applications within the fields of RL and it could definitely be developed further to improve its generalization abilities.

Several extensions proposed by the authors include utilizing a more sophisticated embedding for returns, states, and actions i.e. modeling stochastic settings instead of deterministic returns through conditioning on return distributions. In addition, an alternative approach could be to employ transformers to model the state evolution of a trajectory.

Lastly, we must also be wary of the potential errors a transformer can make. We must avoid datasets that add destructive bias as well as data augmentation with unreliable data. For example, since the DT creates behaviors by conditioning on desired returns, actors that are unstable could lead to unintended results.

Code Repository

All of the code is hosted in the GitHub Repo here

References

[1] Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

[2] Richard S Sutton and Andrew G Barto. Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT Press, (2018).

[3] Chia-Chun Hung, Timothy Lillicrap, Josh Abramson, Yan Wu, Mehdi Mirza, Federico Carnevale, Arun Ahuja, and Greg Wayne. Optimizing agent behavior over long time scales by transporting value. Nature communications, 10(1):1–12, (2019).

[4] Beeching, Edward, and Thomas Simonini. “Introducing Decision Transformers on Hugging Face.” Hugging Face – The AI Community Building the Future., 28 Mar. 2022, https://huggingface.co/blog/decision-transformers.

[5] Aviral Kumar, Aurick Zhou, George Tucker, and Sergey Levine. Conservative q-learning for offline reinforcement learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, (2020).

[6] Aviral Kumar, Justin Fu, George Tucker, and Sergey Levine. Stabilizing off-policy q-learning via bootstrapping error reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00949, 2019.

[7] Yifan Wu, George Tucker, and Ofir Nachum. Behavior regularized offline reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.11361, (2019).

[8] Xue Bin Peng, Aviral Kumar, Grace Zhang, and Sergey Levine. Advantage-weighted regression: Simple and scalable off-policy reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.00177, 2019.

[9] Alec Radford, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. 2018.

[10] Scott Fujimoto, David Meger, and Doina Precup. Off-policy deep reinforcement learning without exploration. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2019.

[11] Aviral Kumar, Justin Fu, Matthew Soh, George Tucker, and Sergey Levine. Stabilizing off-policy q-learning via bootstrapping error reduction. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019.

[12] Noah Y Siegel, Jost Tobias Springenberg, Felix Berkenkamp, Abbas Abdolmaleki, Michael Neunert, Thomas Lampe, Roland Hafner, and Martin Riedmiller. Keep doing what worked: Behavioral modelling priors for offline reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

[13] Aviral Kumar, Aurick Zhou, George Tucker, and Sergey Levine. Conservative q-learning for offline reinforcement learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020.

[14] Rahul Kidambi, Aravind Rajeswaran, Praneeth Netrapalli, and Thorsten Joachims. Morel: Model-based offline reinforcement learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020.

[15] Tianhe Yu, Garrett Thomas, Lantao Yu, Stefano Ermon, James Zou, Sergey Levine, Chelsea Finn, and Tengyu Ma. Mopo: Model-based offline policy optimization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020.

[16] Anurag Ajay, Aviral Kumar, Pulkit Agrawal, Sergey Levine, and Ofir Nachum. Opal: Of- fline primitive discovery for accelerating offline reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.13611, 2020.

[17] Víctor Campos, Alexander Trott, Caiming Xiong, Richard Socher, Xavier Giro-i Nieto, and Jordi Torres. Explore, discover and learn: Unsupervised discovery of state-covering skills. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2020.

[18] Karl Pertsch, Youngwoon Lee, and Joseph J Lim. Accelerating reinforcement learning with learned skill priors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11944, 2020.

[19] Avi Singh, Huihan Liu, Gaoyue Zhou, Albert Yu, Nicholas Rhinehart, and Sergey Levine. Parrot: Data-driven behavioral priors for reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021.

[20] Benjamin Eysenbach, Abhishek Gupta, Julian Ibarz, and Sergey Levine. Diversity is all you need: Learning skills without a reward function. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019.

[21] Kevin Lu, Aditya Grover, Pieter Abbeel, and Igor Mordatch. Reset-free lifelong learning with skill-space planning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.03548, 2020.

[22] Archit Sharma, Shixiang Gu, Sergey Levine, Vikash Kumar, and Karol Hausman. Dynamics- aware unsupervised discovery of skills. In International Conference on Learning Representa- tions, 2020.

[23] Rupesh Kumar Srivastava, Pranav Shyam, Filipe Mutz, Wojciech Jas ́kowski, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. Training agents using upside-down reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.02877, 2019.

[24] Aviral Kumar, Xue Bin Peng, and Sergey Levine. Reward-conditioned policies. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.13465, 2019.

[25] Acting without rewards. 2019. URL https://ogma.ai/2019/08/ acting-without-rewards/.

[26] Tom B Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165, 2020.

[27] Mark Chen, Alec Radford, Rewon Child, Jeffrey Wu, Heewoo Jun, David Luan, and Ilya Sutskever. Generative pretraining from pixels. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1691–1703. PMLR, 2020.

[28] Michael Janner, Qiyang Li, and Sergey Levine. Reinforcement learning as one big sequence modeling problem. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.02039, 2021.

[29] Johan Ferret, Raphaël Marinier, Matthieu Geist, and Olivier Pietquin. Self-attentional credit assignment for transfer in reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.08027, 2019.

[30] Anna Harutyunyan, Will Dabney, Thomas Mesnard, Mohammad Azar, Bilal Piot, Nicolas Heess, Hado van Hasselt, Greg Wayne, Satinder Singh, Doina Precup, et al. Hindsight credit assignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.02503, 2019.

[31] Thomas Mesnard, Théophane Weber, Fabio Viola, Shantanu Thakoor, Alaa Saade, Anna Harutyunyan, Will Dabney, Tom Stepleton, Nicolas Heess, Arthur Guez, et al. Counterfactual credit assignment in model-free reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.09464, 2020.

[32] Jose A Arjona-Medina, Michael Gillhofer, Michael Widrich, Thomas Unterthiner, Johannes Brandstetter, and Sepp Hochreiter. Rudder: Return decomposition for delayed rewards. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.07857, 2018.

[33] Yang Liu, Yunan Luo, Yuanyi Zhong, Xi Chen, Qiang Liu, and Jian Peng. Sequence modeling of temporal credit assignment for episodic reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.13420, 2019.

[34] David Raposo, Sam Ritter, Adam Santoro, Greg Wayne, Theophane Weber, Matt Botvinick, Hado van Hasselt, and Francis Song. Synthetic returns for long-term credit assignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.12425, 2021.

[35] Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

[36] Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

[37] Nicolas Carion, Francisco Massa, Gabriel Synnaeve, Nicolas Usunier, Alexander Kirillov, and Sergey Zagoruyko. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 2020.

[38] Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, 2020.

[39] Vinicius Zambaldi, David Raposo, Adam Santoro, Victor Bapst, Yujia Li,Igor Babuschkin,Karl Tuyls, David Reichert, Timothy Lillicrap, Edward Lockhart, et al. Deep reinforcement learning with relational inductive biases. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018.

[40] Sam Ritter, Ryan Faulkner, Laurent Sartran, Adam Santoro, Matt Botvinick, and David Raposo. Rapid task-solving in novel environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.03662, 2020.

[41] Emilio Parisotto, Francis Song, Jack Rae, Razvan Pascanu, Caglar Gulcehre, Siddhant Jayaku- mar, Max Jaderberg, Raphael Lopez Kaufman, Aidan Clark, Seb Noury, et al. Stabilizing transformers for reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2020.

[42] Chen, Lili, et al. “Decision transformer: Reinforcement learning via sequence modeling.” Advances in neural information processing systems 34 (2021): 15084-15097.

[43] “Introducing Decision Transformers on Hugging Face 🤗.” Hugging Face – The AI Community Building the Future., https://huggingface.co/blog/decision-transformers.